“The highest obligation and privilege of citizenship is bearing arms.” —Gen. George S. Patton

There are so many inspiring, beautiful stories about the great heroes of American history which are scarcely ever told. One happens on them accidentally—buried in a thick, out-of-print biography, in small print on a museum sign, casually and fleetingly mentioned in an obscure educational video. America cannot return to greatness in the future if we do not truly understand the greatness of our past. That is why I am writing an article series to tell a few of these little-known but moving or illustrative “untold stories” of American greatness.

Other articles in this series have included Washington and his army celebrating St. Patrick’s Day; Charity Ferris, unsung heroine of Throgs Neck; and the story behind the “Battle of Princeton” painting by America’s first deaf artist William Mercer. This article includes parts of a shorter piece I wrote for PJ Media. Today, May 20, is Armed Forces Day 2023, part of Military Appreciation Month. To the millions who have served, or continue to serve, thank you—freedom is never free. Today I want to share some inspiring stories of U.S. military heroes.1

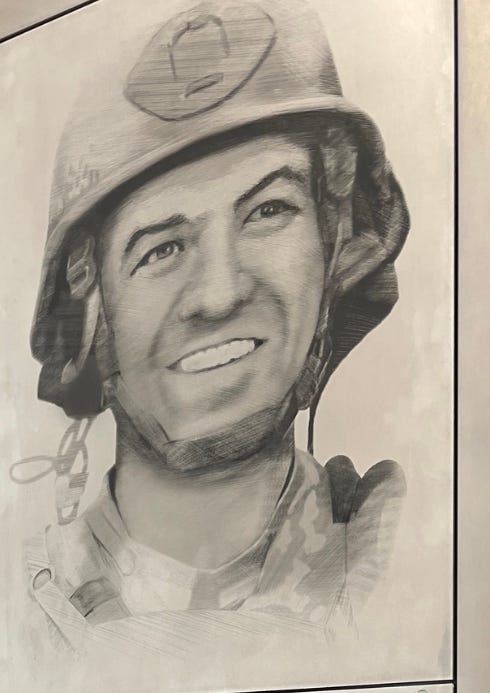

Army hero Bennie G. Adkins’s story is so miraculous and spectacular that it almost seems impossible. Around two thousand North Vietnamese army troops attacked Camp A Shau on 9 March, 1966. The camp was housing at that time 17 American Special Forces soldiers, as well as around 400 South Vietnamese Civilian Irregular Defense Group. “Adkins, then a sergeant first class, killed as many as 175 of the enemy and received 18 wounds during the battle. He then led the wounded to an airstrip for evacuation while evading the enemy.” Unsurprisingly, he received a Medal of Honor for his heroic actions. “I’m just the keeper of the medal for those other 16 who were in the battle, especially the five who didn’t make it,” Adkins said of his astounding courage.

Captain John Callendar was cashiered from the Revolutionary Army for cowardice, but lived to become a hero of the American cause. Last year, I learned the story of John Callendar from a reenactor at George Washington’s Mt. Vernon. At the Battle of Bunker Hill, Callendar and his artillery company fled in panic from the British. He was court-martialed, removed of rank, and cashiered from the Revolutionary Army. But Callendar’s story didn’t end there. He humbly re-enlisted in the same artillery company which he had previously commanded. At the Battle of Long Island, the British and Hessians killed all the men around Callendar and then charged him with fixed bayonets. Callendar did not budge an inch. He continued to fire until he was captured by the British. Later, he was returned to the Revolutionaries through a prisoner exchange, restored to rank, and served honorably throughout the rest of the Revolution.

Air Force hero Daniel “Chappie” James Jr. was among the original Army Air Corps Tuskegee Airmen when he trained the famous “Red Tails” squadron. He saw his first combat during the Korean War, flying 101 combat missions. During Vietnam, he flew 78 missions as vice commander of the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing. According to Military.com, “In the 8th TFW, he served under none other than then-Col. Robin Olds, including during Operation Bolo, the highest single MiG sweep ever. The duo were so successful, their men nicknamed the team ‘Blackman and Robin.’” James reportedly almost shot Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi during a stand-off while he was commanding a U.S. Air Force Base in Libya. Daniel “Chappie” James was the first black American to become a four-star general.

Eddie Rickenbacker is more famous than many of the other heroes in this article. The race car driver who taught himself to fly joined the military as soon as the United States joined World War I. Military.com notes that, within a year’s time, Rickenbacker had been promoted to officer and had already shot down his fifth enemy aircraft, “earning him the title of ‘Ace.’” By a year after that, Rickenbacker was in command of his whole Aero Squadron. “By the time of the Nov. 11, 1918 armistice, Rickenbacker racked up 26 aerial victories, a record he held until World War II. His tactic was to charge right at enemy flying squads, whatever the odds, winning every time,” Military.com explains. “Rickenbacker was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross with six oak leaf clusters, the Croix de Guerre with two palms, the French Legion d'Honneur and was later awarded the Medal of Honor.”

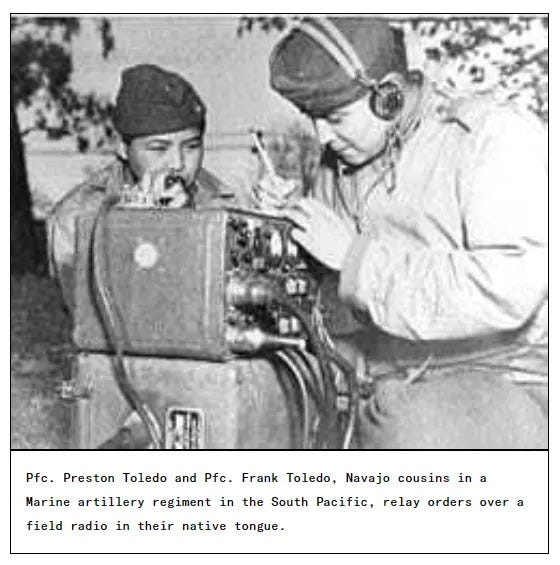

Sometimes whole groups, regiments, or battalions within the U.S. military have shown exceptional heroism. These include the all-black (including all-black officers) 370th Infantry in WWI, whose outstanding courage in battle earned them the nickname “Harlem Hellfighters” and the prestigious French military award, the Croix de Guerre. Then there’s the famed Navajo Code Talkers whose work proved so key to WWII operations including Iwo Jima. And don’t forget the Marbleheaders (Washington’s “Indispensables”) or Maryland’s “Immortal 400” of the Revolutionary War.

1st Lt. Sharon A. Lane was the only Army nurse killed in the Vietnam War “as a direct result of hostile fire.” A rocket hit the ward where she was caring for patients on 8 June, 1969, less than 10 weeks after her arrival in Vietnam. She was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star Medal for heroism.

SFC Leroy A. Petry was serving in Afghanistan in May 2008 when he was shot in both thighs by insurgents. Then an enemy grenade landed near Petry and two fellow Army Rangers. Petry threw the grenade back, saving his fellow Rangers, but the grenade exploded just as it left his right hand. That didn’t stop Petry. In May 2010, he raised his prosthetic hand to reenlist as an Army Ranger. Petry received the Medal of Honor.

While visiting the Freedom Museum in Manassas, Virginia last year, I came across the stories of Navy hero Dorie Miller and Army Air Force (or Army Air Corps) hero William Thomas Anderson. Both performed heroic actions during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that pushed America into World War II, and both died during the war. Mess Attendant Second Class Dorie Miller was on the USS West Virginia that fateful Dec. 7, 1941. Despite enemy strafing and bombing, and severe fire, Miller moved his mortally wounded captain to a safer place and then operated a machine gun until he was ordered to leave the bridge. While he survived that day (unlike 66 other sailors who went down with the USS West Virginia), he was on the Liscome Bay when it was sunk by a Japanese submarine on November 24, 1943. He was presumed dead a year later. Miller was the first black American to be awarded the Navy Cross.

Meanwhile, U.S. Army Air Force Corporal and Radio Operator William Thomas Anderson was one of the first casualties of World War II when he was mortally wounded during the Pearl Harbor attack. “While on duty as a radio operator Corporal Anderson voluntarily obtained a sub-machine gun and with utter disregard for his own safety took position in the open field without cover and continued to fire at enemy planes which were bombing and strafing the field, until he was mortally wounded. His unquestionable valor at the cost of his life is in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service.” He was awarded the Certificate of Honor, Army Air Force, the Purple Heart and Distinguished Service Cross.

Sgt. Chikara “Don” Oka said of World War II, “For us it was a civil war.” Oka and his six brothers were all ethnically Japanese, but born American citizens. Five of them served in WWII, when Japanese Americans were being persecuted, distrusted, and locked in internment camps because Japan was America’s enemy. Even more personally for Oka, two of his brothers living in Japan when Pearl Harbor was bombed were drafted into the Japanese military. For the Oka family, WWII really was a civil war. Don Oka was trained in the U.S. Army Military Intelligence Service and during the Aleutian Campaign of 1942 he served with the Alaskan Scouts on Kiska Island. During that campaign, he translated captured documents and also interrogated prisoners. He ultimately served on “Saipan and the Tinian Islands during the Marianas Campaign.” With so many reasons to be disloyal to America, Oka’s loyalty was especially praiseworthy.

If you haven’t heard the story of James Armistead Lafayette, the brilliant slave-turned-Patriot double agent whose spy work was so essential to the American Revolution’s success, you should. He completely outwitted the British and provided information vital to the decisive American victory at Yorktown.

Col. William Trimble is known to history not for his battlefield exploits during the Civil War, but for his actions off the battlefield. It was an official policy of the Confederate government for its forces to enslave or kill every “escaped slave,” particularly captured black Union troops. In practice, this meant that the Confederate Army rounded up nearly every black man, woman, and child it could seize (white officers of black Union troops were also ordered executed—see the Retaliatory Act). But when the Confederates took over Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, in September 1862, Union Col. Trimble took a firm stand against the Confederates, as a sign at Harpers Ferry relates:

[The] Confederates captured the remaining 12,500 Union soldiers. Among them were free black laborers, working for Union Colonel William Trimble’s regiment…Confederate soldiers began dragging the free black laborers away, falsely claiming the Union was ‘stealing their slaves.’ Colonel Trimble shouted ‘My men are unarmed—I am not. Unhand them!’ Then he ordered ‘Regiment march,’ swiftly moving both the laborers and the soldiers past the Confederate guards, down this ramp, and across the bridge to safety in the North.

Brig. Gen. Samuel B. Webb fought at the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775 and went on to serve in the Army throughout the American Revolution. “Four men were shot dead within five feet of me; but, thank Heaven, I escaped with only the graze of a musket ball on my hand,” Webb recalled of Bunker Hill. He was wounded again at White Plains while serving as an aide to Gen. George Washington, and was wounded yet again at Trenton in 1776. Nothing daunted, Webb raised and equipped the 9th Connecticut Regiment in 1777. He was captured during a raid on Long Island but was returned during a 1781 prisoner exchange, after which he commanded two new light infantry regiments as a brigadier general. Webb was always completely dedicated to the cause of liberty.

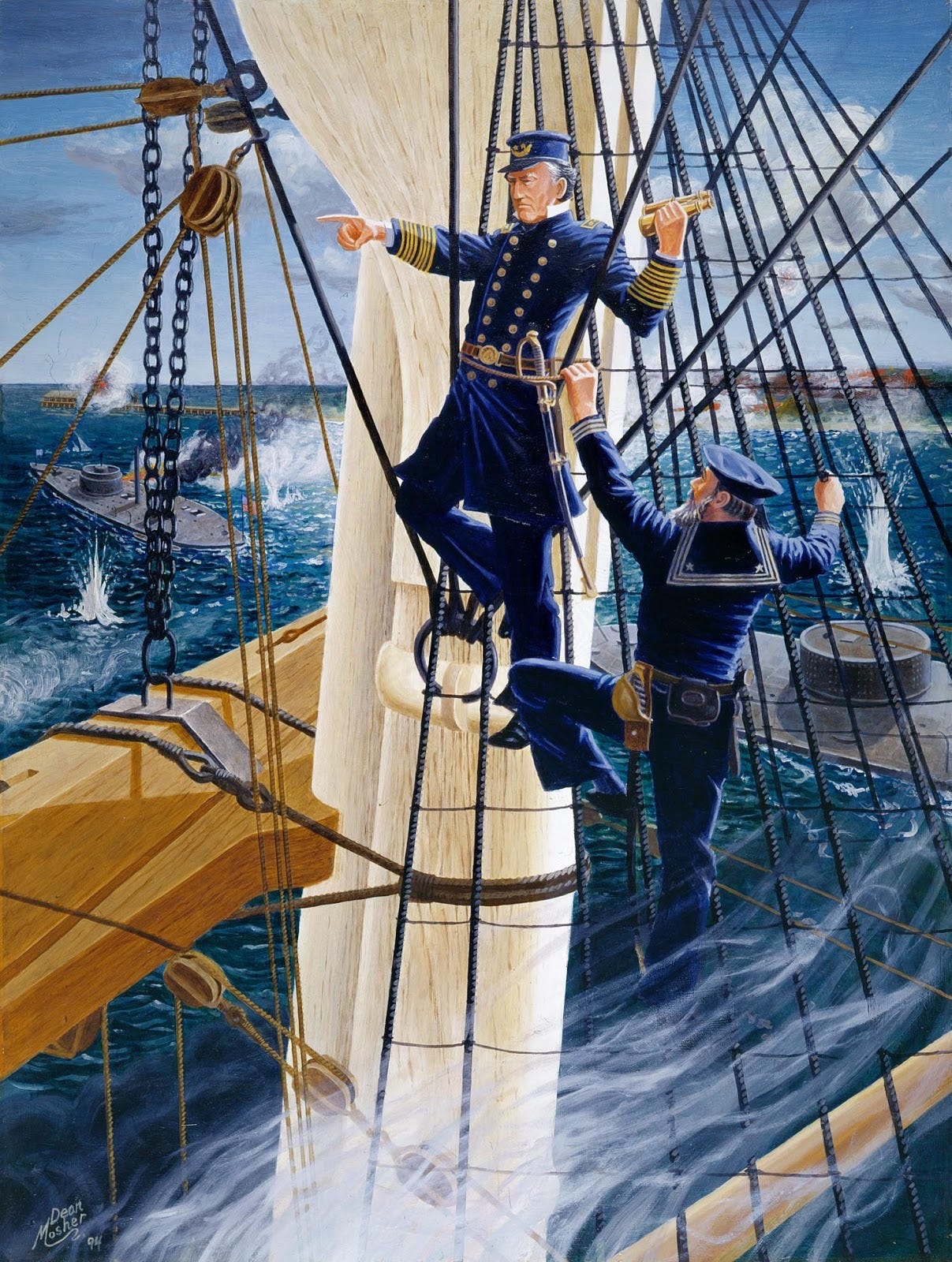

Admiral David Farragut, son of a Spanish-born merchant mariner, was the Navy’s first full admiral. He became famous for his actions during the Civil War’s 1864 Battle of Mobile Bay, when he ignored Confederates mines and led his squadron of ships to victory with the famous words, “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!”

We all know the famous image of the Marines raising the American flag on the blood-soaked soil of Iwo Jima during World War II, but few people know the names of the Marines in that photo. PFC Ira H. Hayes was a Pima Native American Indian, a U.S. Marine, and one of the men in the world-famous flag-raising photo. Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz said of the Iwo Jima conflict, “Among the Americans serving on Iwo island, uncommon valor was a common virtue.” It is no wonder Hayes and his fellow Marines have inspired people for generations.

Speaking of Iwo Jima, the National Museum of the Marine Corps tells the story of teenaged hero Jacklyn Lucas:

Just a few days after his 17th birthday, Private First Class Jacklyn H. Lucas was creeping through a twisted ravine on Iwo Jima with three other men from his rifle team when they were ambushed by the Japanese. As the men jumped in foxholes, two grenades landed near Lucas. Without hesitation, Lucas threw himself on top of both grenades. One of the grenades exploded wounding Lucas' right arm and wrist, right leg and thigh, and chest. For his actions, Lucas was awarded the Medal of Honor, making him the youngest Marine and service member to receive the medal in World War II.

America’s Armed Forces are, and always have been, filled with heroes. It is their sacrifice that is the price of our freedom. God bless our troops, and God bless America.

Multiple stories and images are from the National Museum of the United States Army