St. Valentine and Self-Sacrifice as the Truest Expression of Love

“Greater love than this no man hath, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” —Jesus Christ (John 15:13)

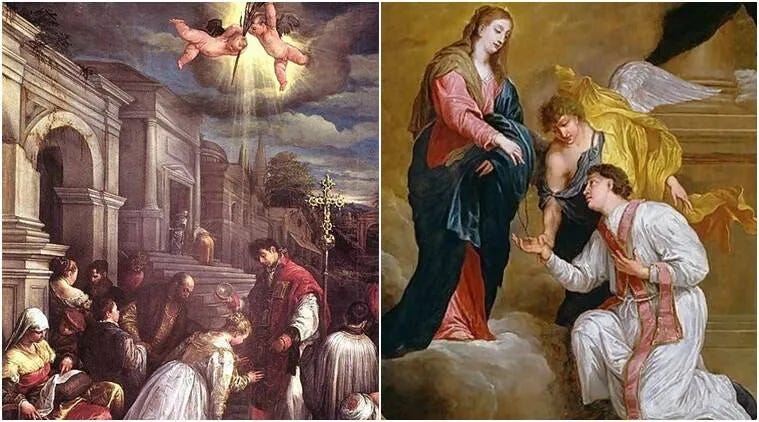

Today is the feast of St. Valentine of Rome, the namesake of the popular romantic holiday of Valentine’s Day, and of the famous Slavic evangelists Sts. Cyril and Methodius. There are many heart-warming and lovely secular practices now surrounding this day, but I wanted to share a short meditation on what the life of the saintly namesake of this holiday teaches us about the true nature of love—and how it is best expressed.

Sadly, for a saint whose name has become so famous even among non-Christians, there is not much that we know for complete certainty about St. Valentine’s life. Some scholars have now tried to claim that St. Valentine of Terni (whose feast is also today) and the famous St. Valentine are actually the same person, but since the former was a bishop and the latter has for a long time been celebrated in the Catholic Church as a priest (for instance, the pre-Vatican II Mass propers of the day are specifically for a non-bishop), and the calendar was consistent for centuries listing them separately, I am skeptical of this assessment.1

In any case, whatever the truth about the two St. Valentines, the famous St. Valentine was certainly a cleric, who was martyred for the faith in Roman persecutions in the 3rd century. And the stories told of his life explain why this priest became such a patron for romantic love—but also for loving relationships of all kinds.

“Father Frank O’Gara of Whitefriars Street Church in Dublin, Ireland, tells the real story of the man behind the holiday—St. Valentine.

‘He was a Roman Priest at a time when there was an emperor called Claudi[u]s who persecuted the church at that particular time,’ Father O'Gara explains. ‘He also had an edict that prohibited the marriage of young people. This was based on the hypothesis that unmarried soldiers fought better than married soldiers because married soldiers might be afraid of what might happen to them or their wives or families if they died.’

‘I think we must bear in mind that it was a very permissive society in which Valentine lived,’ says Father O'Gara. ‘Polygamy would have been much more popular than just one woman and one man living together. And yet some of them seemed to be attracted to Christian faith. But obviously the church thought that marriage was very sacred between one man and one woman for their life and that it was to be encouraged. And so it immediately presented the problem to the Christian church of what to do about this.’

‘The idea of encouraging them to marry within the Christian church was what Valentine was about. And he secretly married them because of the edict.’

Valentine was eventually caught, imprisoned and tortured for performing marriage ceremonies against command of Emperor Claudius the second. There are legends surrounding Valentine’s actions while in prison.

‘One of the men who was to judge him in line with the Roman law at the time was a man called Asterius, whose daughter was blind. [Valentine] was supposed to have prayed with and healed the young girl with such astonishing effect that Asterius himself became Christian as a result.’

In the year 269 AD, Valentine was sentenced to a three part execution of a beating, stoning, and finally decapitation all because of his stand for Christian marriage. The story goes that the last words he wrote were in a note to Asterius' daughter. He inspired today’s romantic missives by signing it, ‘from your Valentine.’

‘What Valentine means to me as a priest,’ explains Father O’Gara, ‘is that there comes a time where you have to lay your life upon the line for what you believe. And with the power of the Holy Spirit we can do that —even to the point of death. . .If Valentine were here today, he would say to married couples that there comes a time where you’re going to have to suffer. It’s not going to be easy to maintain your commitment and your vows in marriage. Don’t be surprised if the ‘gushing’ love that you have for someone changes to something less ‘gushing’ but maybe much more mature. And the question is, is that young person ready for that?’”

And there you have it—the origin of valentines and the reason St. Valentine of Rome is associated with marriage and romance. Fr. O’Gara’s reflections on St. Valentine’s life provide me with a segue to a reflection on what love most truly means.

Back in 2020, before Covid shutdowns ended my brief stay in Rome, I was able to visit the church where St. Valentine’s skull is preserved. Seeing that skull on Valentine’s Day was not a ghoulish or morbid experience—it was a joyous one, a reminder that self-sacrificial love extends beyond death and that those who love God and their neighbor in this world will live in eternal happiness in the next life. True love—romantic, filial, fraternal, parental, or amicable—is, by its very nature, self-sacrificial and eternal. “For God so loved the world, as to give his only begotten Son; that whosoever believeth in him, may not perish, but may have life everlasting,” Jesus Christ told us (John 3:16).

And how did Christ save the world? Through His death. When Catholics say that Jesus was born to die, that is not morbid; it is an awe-inspiring truth. God so loved the world that He became man so that He could die and thus ensure that those of us doomed to death by sin might live. The bleeding, broken Christ on a cross is the greatest image of love that this world has ever seen. The greatest act of love ever performed in history was the death of the God-man. Love is good and true and enduring only to the extent that it is giving. Only those willing to sacrifice for the beloved are truly in love.

This is a truth exemplified in the life of St. Valentine himself. St. Valentine was certainly not opposed to joyous romance and passionate love between man and woman—he was executed for performing marriage ceremonies. St. Valentine clearly believed that romantic love was a necessity, a thing so holy that he was willing to die for blessing it. St. Valentine not only blessed romantic love, he exhibited a (non-romantic) love for his flock that led to his death. His love for his fellow Christians was so strong and true that he paid the ultimate sacrifice because of it.

And those Christian couples St. Valentine married also sacrificed something—they sacrificed the ability to have many romantic partners in a sexually licentious society, and they risked the wrath of the civil authorities for violating the wicked edict. Christianity teaches that “God is love” (1 John 4:8), and God is Love because He is, though one, mysteriously also a community—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—three Persons in one God, distinct by their relations to each other. Theology teaches that the Holy Spirit IS the love, or the product of the love, between the Father and the Son, for instance.

This holy love was also exemplified in the lives of Sts. Cyril and Methodius. They gave up a great deal to go evangelize in foreign lands and give those peoples an alphabet, a written language, and unique liturgy. Love is an action, not a feeling, and often an unglamorous action. Those many long hours Cyril and Methodius spent at their work, both evangelizing and creating written Slavic, were hardly romantic or exciting, but that work changed the world. Until we are willing to do hard, painful work even when we don’t feel like it, we will never be able to love properly. But it is that love that is demanded both for human relationships and a relationship with God.

This all leads me to my final point, which is that love is self-giving precisely because it sacrifices a lower good for a higher good. Why do we give valentines and flowers and chocolates and other presents on St. Valentine’s Day? Because humans instinctively know that love is only love when it provides visible signs. Jesus said that not everyone who calls Him “Lord” will enter Heaven (Matt. 7:21). To put it another way, the man who claims to love another but will always sacrifice that other to his own desires and convenience, or the man who never once does something kind for his “beloved,” is a liar. Love is action. And yet the mystery of love is that, by giving, one receives. Married couples sacrifice the chance to have many partners for exclusivity with one—and so experience a deeper, more lasting, and more satisfying love than that experienced by those who have a new romantic partner every month.

Why do even atheists admire stories where one lover or both lovers go through many trials, risk danger, or even die for the sake of the beloved? Why is Romeo and Juliet a touted romance, when it ends in premature death? Why is Prince Phillip such a hero for fighting the dragon and hacking through the thorn forest to reach Sleeping Beauty? Why did Psyche have to go through many trials before she could be the eternal bride of Cupid? Why is Mr. Darcy’s saving of Elizabeth Bennett’s sister such a proof positive to Elizabeth that he must certainly love her? Why did Christ say that “Greater love than this no man hath, that a man lay down his life for his friends?” We all know, instinctively, that only the love willing to risk everything is truly admirable. In every age, on every continent, humans have understood this.

And yet we also admire these stories because we believe that those lovers achieved an envied state, had a priceless experience, which was worth even death to have possessed. The Little Mermaid (in the original tale) dies sacrificing herself for the man she loves, but she gains a soul—and thus eternal life. The lovers in the old fairy tales only lived “happily ever after” because they were willing to endure suffering first. The Christian martyrs went singing to their deaths because they knew that after martyrdom came everlasting union with Divine Love. What a truth it is that it is better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all!

(I originally published this article last year.)

It is an unfortunate tendency of modern scholars, even those who are religious, to assume that any story or saint about whom legends were told or whose life story is not 100% verifiable according to their personal arbitrary standards is a myth only. St. Dorothy, who was celebrated for over a thousand years as a saint and martyr in the Catholic Church, has been incredibly pronounced a mere legend even by Catholics in modernity.

didn't read it.

self-sacrifice may be appropriate for raising a family or fighting off Mongols invading your village, but it is the single most neurotic-making evil in our society.

they say, "It isn't about you." oh yes it is.

people should not be ashamed of their natural desires and should not flee from the hint of life being selfish, but this hypocritical refrain makes dunderheads of the masses.