“To refuse to fight would have been to lose; to fight is to win. We have kept faith with the past, and handed on its tradition to the future.” —Padraig Pearse

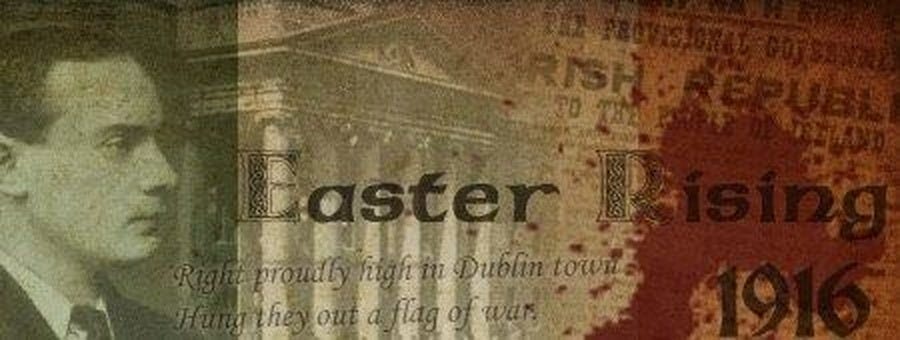

On Nov. 10, 1879, an Irish boy was born, who would go on to become one of Ireland’s greatest and most inspirational independence leaders, whose 1916 uprising against the English and brave death at their hands kept Ireland’s fighting spirit alive for generations. That boy was Padraig Pearse.

Padraig or Patrick reflected in his own person the uneasy union of England and Ireland in that his father was English while his mother was Irish. But despite his English father, Pearse always knew on which side his loyalties would lie, he knew which country was the tyrant and which the victim that needed to escape tyranny to flourish. Not that Pearse ever bore himself as a victim, for he was noble and courageous despite any crisis.

But perhaps those who knew him when he was young would not have anticipated his future glorious reputation, for he was always reserved and inclined to avoid much interaction with other people, particularly females, possibly because he was not confident in his appearance—Irish Central notes that the otherwise handsome young man had a cast in his right eye. Or perhaps, like other great thinkers, he simply preferred to keep his words and thoughts to himself until the right time.

Pearse at different times was a newspaper editor, an educator, and a soldier. He founded the Scoil Éanna (St. Enda’s School) and did a speaking tour of America to raise money, as Irish Central notes. He was originally more moderate politically, but the failure of Home Rule drove him to the Irish Volunteers. When some of the so-called radicals in the Irish independence movement heard Pearse speak, they were astounded and delighted. Here was a man who could raise popular support, who could inspire troops and lead them into battle. During a 1915 funeral oration, standing beside two men who would later share his fight and his fate with him, Pearse defiantly challenged the British oppressors:

“The defenders of this realm have worked well in secret and in the open. They think that they have pacified Ireland. They think that they have purchased half of us, and intimidated the other half. They think that they have foreseen everything. They think that they have provided against everything; but the fools, the fools, the fools! they have left us our Fenian dead, and while Ireland holds these graves, Ireland unfree shall never be at peace.”

And so on Easter Monday of 1916, the young Pearse found himself President of the Provisional Government and as Commandant-General was Commander-in-Chief of the Irish Volunteers. The Easter Rising had begun, and Pearse stood on the steps of the General Post Office of Dublin to read the Irish Declaration of Independence that he had written, which you can read at Irish Central. This document inspired the Irish, but it infuriated the British.

Read Also:‘A Terrible Beauty’: Ireland’s Easter Rising, 1916

After days of brutal fighting, and with the post office on fire, Pearse and the other leaders had to escape. They soon recognized that they had no other option than to surrender if they wanted the bloodthirsty British not to massacre Dublin’s civilians. And so, though they were brave and defiant even yet, they surrendered to save the lives of others.

While in prison, Pearse was still reserved and silent, according to Irish Central. He knew, of course, what his fate would be. The British would certainly kill him. But he had fought bravely, he was a devout Catholic, and he believed he could pass to a better and juster life after death. At this point, his self-sacrificial focus was to save others if possible from sharing that death. In his own words at his court-martial:

“My sole object in surrendering unconditionally was to save the slaughter of the civil population and to save the lives of our followers who had been led into this thing by us. It is my hope that the British Government who has shown its strength will also be magnanimous and spare the lives and give an amnesty to my followers, as I am one of the persons chiefly responsible, have acted as C-in-C and president of the provisional government, I am prepared to take the consequences of my act, but I should like my followers to receive an amnesty. I went down on my knees as a child and told God that I would work all my life to gain the freedom of Ireland. I have deemed it my duty as an Irishman to fight for the freedom of my country.”

Indeed, though the Easter Rising did not succeed in its object of bringing Ireland immediate independence, even though Pearse and his fellows would be executed by the British, they had not been defeated. Their spirits lived on after their deaths, inspiring new generations of freedom fighters until, only a few years later, Ireland finally achieved independence. As Pearse himself said, “To refuse to fight would have been to lose; to fight is to win. We have kept faith with the past, and handed on its tradition to the future.”

He made that speech at the grave of O’Donovan Rossa, an old Fenian who had been exiled to the USA. O’Donovan died in New York 35 years later and the British gave permission to have him returned. If only they had known what they were doing - less than 12 mths later came the Easter Rising and the War of Independence.

Today, in Northern Ireland, they still quote, “while Ireland hold these graves, Ireland unfree will never be at peace.”