On Easter Monday of 1916, a group of Irishmen led an uprising against the British. The freedom fighters dreamed of an independent Ireland, but sadly the rising quickly turned very bloody and the leaders were executed by the British, who brutally suppressed the rising. It was this event which Irish poet William Butler Yeats commemorated in his poem “Easter. 1916,” when he wrote of the Irish rebels, “A terrible beauty is born.”

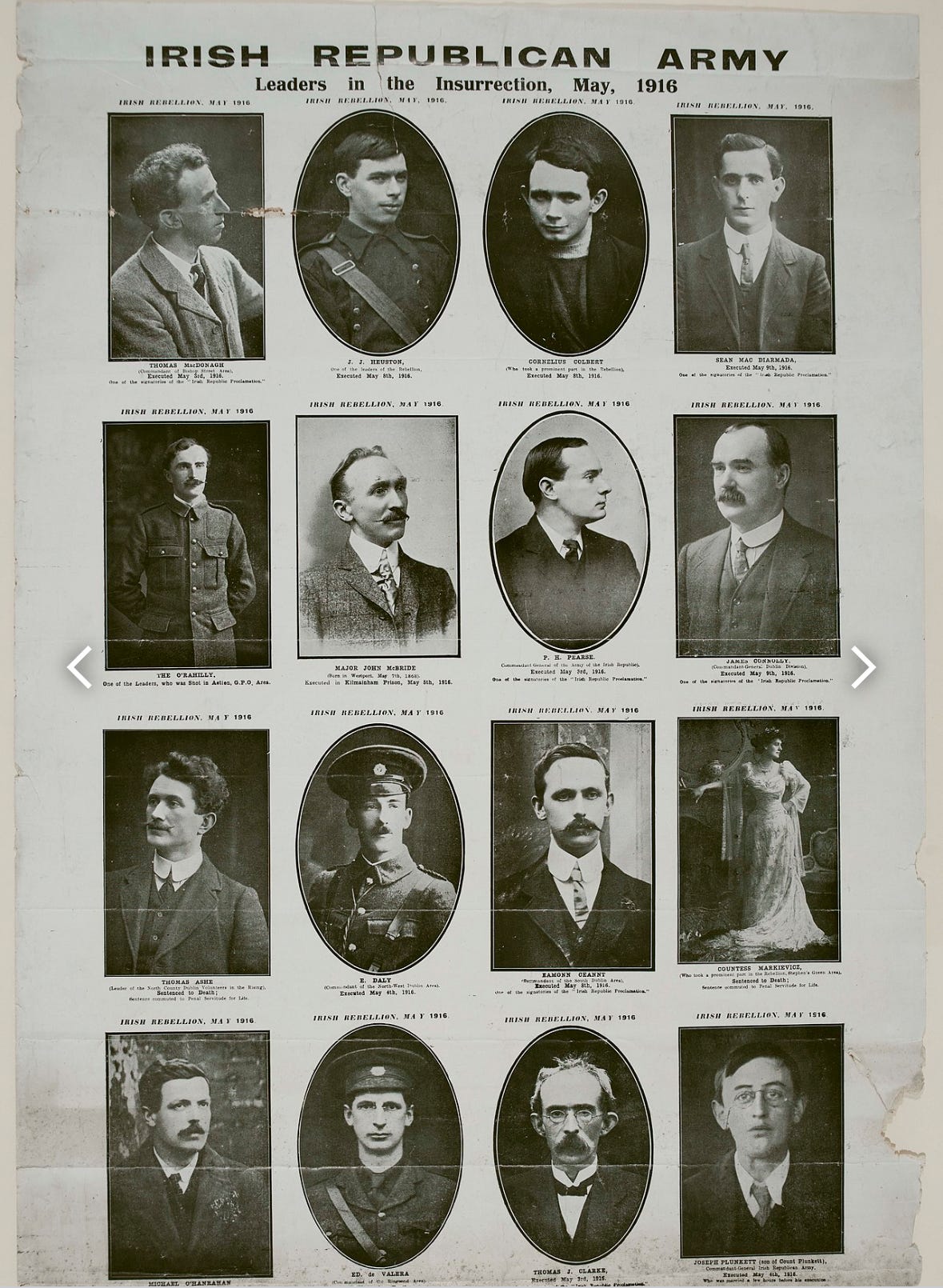

On April 24, the Irish Republican fighters captured the Dublin General Post Office and other points in the city and Padraig Pearse read a proclamation declaring the start of an Irish Republic. The British were determined to stamp out the rising, and the leaders surrendered on April 29 to stop the bloodshed. Pearce and 14 other leaders of the Easter Rising were executed soon after. Ironically, though many Irishman had not been strongly in sympathy with the initial rising, the executions of the Irish Republicans sparked a wave of nationalist fervor in Ireland. By dying, the heroes of the rising helped ensure that other Irishman would fight, and fight successfully, to achieve their final independence from Britain.

Yeats, generally not a very political man, said of the Easter Rising and its results, “I had no idea that any public event could so deeply move me.” In the aftermath of the brief uprising and British suppression, Yeats turned to poetry. The poet’s modernist, somewhat nihilist philosophy is evident in the early stages of the poem, and in his sad contemplation of whether the heroes of the rising died in vain. Yet, ultimately, he immortalizes the heroes for future generations.

No heroic death is ever in vain. The men who bravely fought and tragically died in the Easter Rising inspired thousands or possibly millions of future Irishmen, who would take up their cause and eventually achieve the independence of Ireland from Great Britain. It is fitting that the Easter Rising, aiming for Irish freedom, occurred during Easter week, right after the commemoration of Jesus’s death that brought spiritual freedom to all mankind.

Below is Yeats’s poem in full. Even in the midst of a modernist world that seems bereft of hope, let us too look to the brave freedom fighters of the past to inspire us:

‘I have met them at close of day

Coming with vivid faces

From counter or desk among grey

Eighteenth-century houses.

I have passed with a nod of the head

Or polite meaningless words,

Or have lingered awhile and said

Polite meaningless words,

And thought before I had done

Of a mocking tale or a gibe

To please a companion

Around the fire at the club,

Being certain that they and I

But lived where motley is worn:

All changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

That woman's days were spent

In ignorant good-will,

Her nights in argument

Until her voice grew shrill.

What voice more sweet than hers

When, young and beautiful,

She rode to harriers?

This man had kept a school

And rode our wingèd horse;

This other his helper and friend

Was coming into his force;

He might have won fame in the end,

So sensitive his nature seemed,

So daring and sweet his thought.

This other man I had dreamed

A drunken, vainglorious lout.

He had done most bitter wrong

To some who are near my heart,

Yet I number him in the song;

He, too, has resigned his part

In the casual comedy;

He, too, has been changed in his turn,

Transformed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

Hearts with one purpose alone

Through summer and winter seem

Enchanted to a stone

To trouble the living stream.

The horse that comes from the road,

The rider, the birds that range

From cloud to tumbling cloud,

Minute by minute they change;

A shadow of cloud on the stream

Changes minute by minute;

A horse-hoof slides on the brim,

And a horse plashes within it;

The long-legged moor-hens dive,

And hens to moor-cocks call;

Minute by minute they live:

The stone's in the midst of all.

Too long a sacrifice

Can make a stone of the heart.

O when may it suffice?

That is Heaven's part, our part

To murmur name upon name,

As a mother names her child

When sleep at last has come

On limbs that had run wild.

What is it but nightfall?

No, no, not night but death;

Was it needless death after all?

For England may keep faith

For all that is done and said.

We know their dream; enough

To know they dreamed and are dead;

And what if excess of love

Bewildered them till they died?

I write it out in a verse—

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.’