Happy July 4th: Iconic and Inspiring Images of Americans Throughout the Centuries

While it is true that many of the ideals of America were ideals throughout history, particularly in Judeo-Christian cultures, it was only in America that these ideals saw a practical fruition. There are other countries that have had their great heroes and events, but only America was founded on a philosophy and set of principles so great, that if one is a tyrant or otherwise wicked, one automatically ceases to adhere to these American principles. Today is the day to be proud that we live in the greatest country that has ever existed, the United States of America.

For that reason, I want to share a few iconic and inspiring images of Americans throughout the centuries.

The first Thanksgiving is an illustration of what is best about America even before it was a separate nation—settlers and native Indians celebrating their comeback from a harsh winter of death and starvation by praying to God and eating together in friendship.

Especially on this day, we must never forget our founding principles. Below are paintings of the signing of the Declaration of Independence and of the Constitution, a reminder of how “We the people” declared our independence to defend our rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Emmanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware is arguably the most iconic—and the most illustrative—American masterpiece. It is an idealized depiction of Gen. George Washington crossing the icy and treacherous Delaware River on Christmas Night, 1776 to take the Hessian garrison at Trenton by surprise and win a significant and much-needed victory for the Revolutionary cause. From the ethnic/racial diversity of the boat’s crew, to the flag proudly held by a young James Monroe, to the embodiment of Washington the charismatic and visionary leader, to the determination to beat all odds—this painting is truly the representation of all that is best about America.

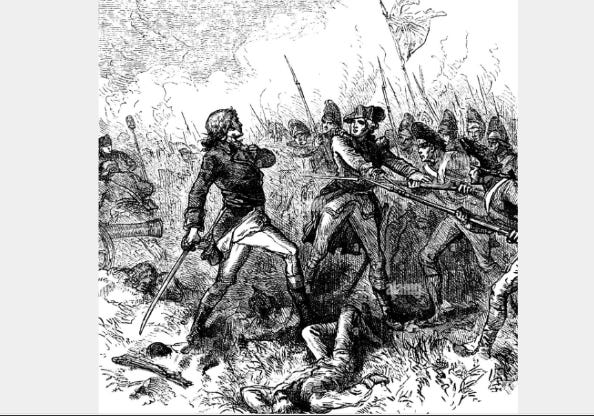

I just wrote an Untold Stories article about the amazing story of John Callendar. As the captain of an artillery company at the Battle of Bunker Hill, Callendar panicked in the face of British troops and fled with his men. Cashiered out of the army in shame for cowardice, Callendar re-enlisted and, at the Battle of Long Island, heroically refused to abandon his post, firing at the enemy even when every other member of his company was dead and the British and Hessians were rushing him with fixed bayonets. Impressed by his extraordinary bravery, the British spared his life and Callendar was eventually returned to the American Army. He served throughout the war as a brave and honorable Patriot soldier. Below is a depiction of his heroic stand against the British and Hessians:

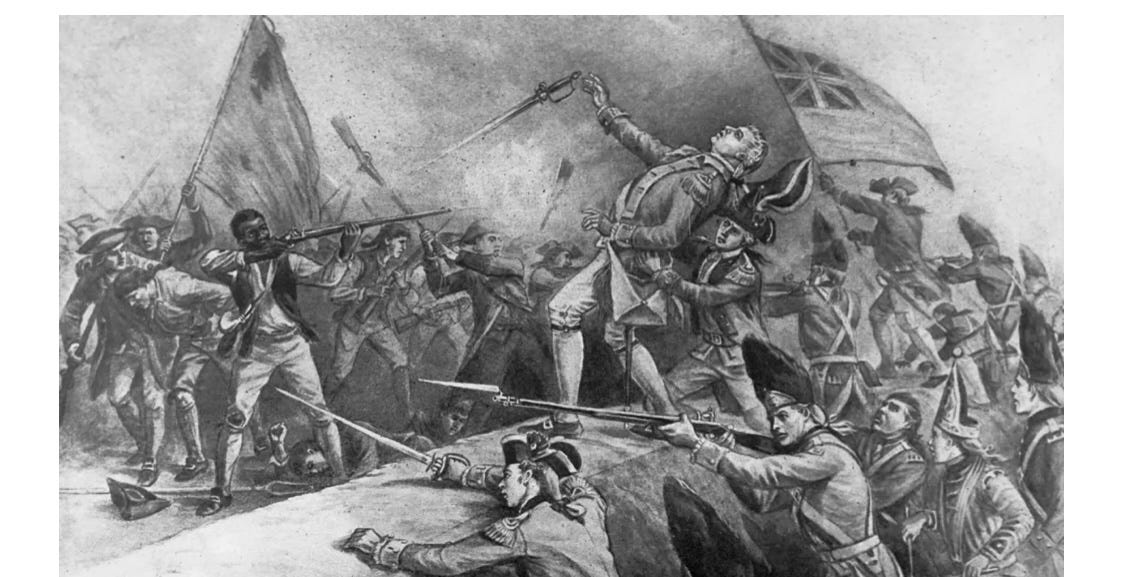

Peter Salem was born a slave, and he was still a slave when he fought as a “minute man” in the opening shots of the Revolution at Lexington and Concord. Freed by his owners so that he could continue fighting for the Patriots, Salem made his mark in history at the Battle of Bunker Hill, in an action whose result is believed to be depicted in John Trumbull’s The Battle of Bunker Hill painting. Salem is said to have killed one of the important British officers at the battle, Major John Pitcairn, just as he was coming over the top of the American redoubt with a demand that the defenders surrender. It is that brave deed depicted in this image.

During the important naval Battle of Mobile Bay in the Civil War, Union Admiral David Farragut made the daring and seemingly foolish decision to run his ships right through a Confederate minefield so she could attack a well-defended Confederate point. The admiral’s gamble paid off and his command to enter the minefield has gone down as one of the most famous quotes in American history, “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!”

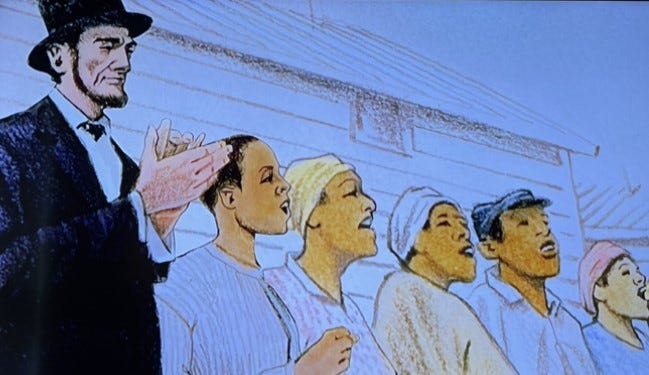

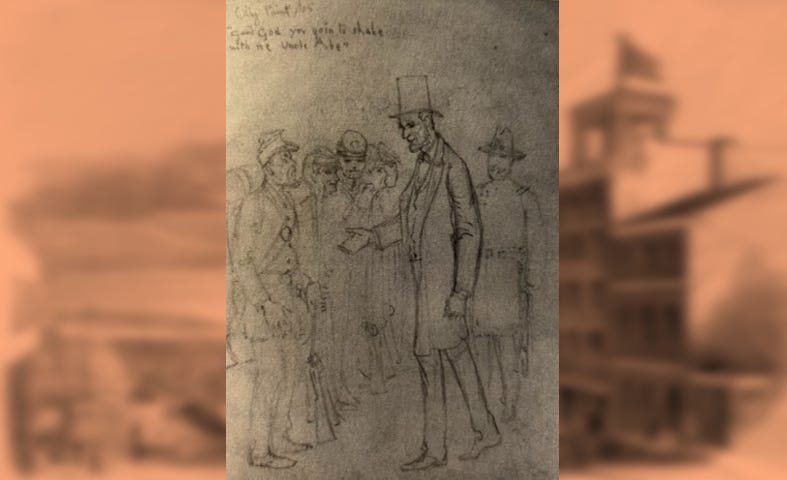

In another Untold Stories article, I recounted Abraham Lincoln’s visits to the “contraband” camps of former slaves toward the end of the Civil War. Lincoln’s views on the importance of complete civil rights for black Americans had been changing for the better throughout his presidency, and his visits to the “contraband” camps may have influenced that. Witnesses identify two visits of Lincoln’s to the camps, during one of which Lincoln sang songs with the former slaves and was moved to tears. The first image shows Lincoln singing in fellowship with the former slaves.

The second image is a from-life sketch an artist did of Lincoln shaking the hand of a black Union soldier at Richmond, when he came at the end of the Civil War to inspect the captured Confederate city. Slaves who had just been freed (some mere hours before) by the Union troops hailed Lincoln as their savior, and Lincoln made them a beautiful speech, declaring, “‘Liberty is your birthright. God gave it to you as he gave it to others, and it is a sin that you have been deprived of it for so many years.’”

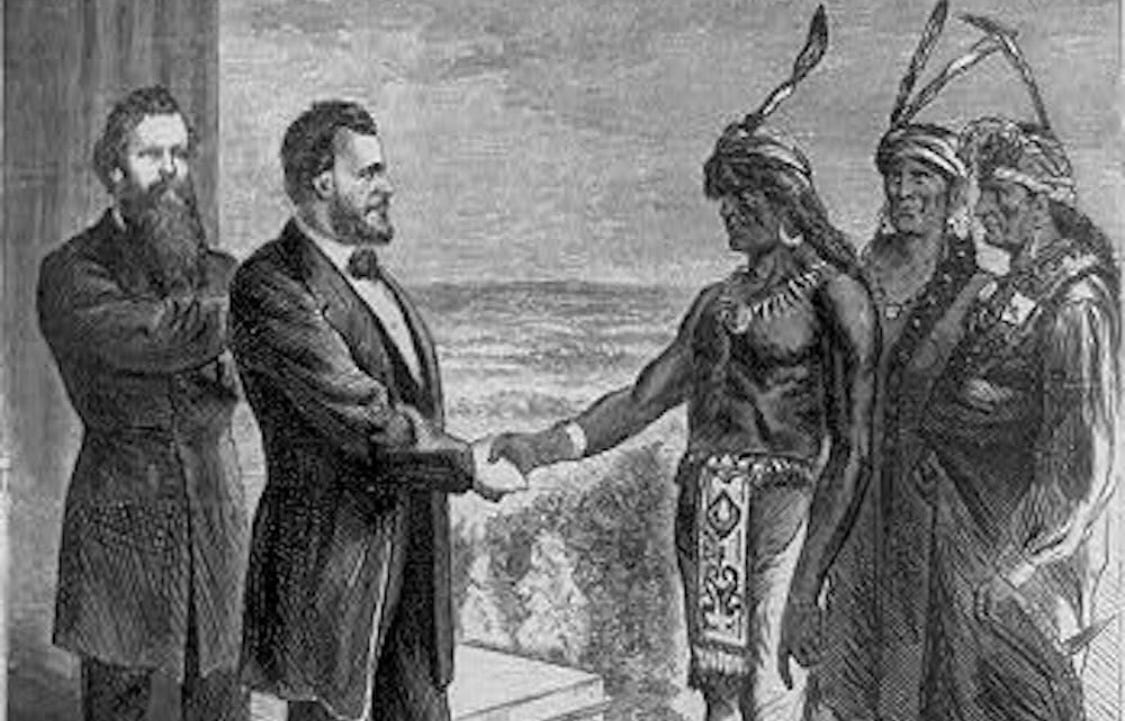

Ulysses S. Grant has received a much harder rap as both general and president in modernity than he deserved. In fact, he was so good a general that even the spy set upon him by the War Department was soon ready to vow he was a military genius; and, as president, he was arguably the greatest champion of civil rights ever to have held that office. One of the areas in which Grant was uniquely admirable was his very good relations with Native American Indian tribes. While other government officials unfortunately did not hold to Grant’s friendly policy with the native tribes, a Sioux chief testified to Grant’s personal friendship with his tribe when he told President Grant (running for re-election), “I hope you may be successful [in the election]. This would please me very much, for you have been very kind to my people.”1

We are a nation of immigrants. Whether our ancestors came here in the 1600s or the 1900s, whether we were born here in the US or thousands of miles away, whether we are Chinese or Irish or Greek or Ugandan, our belief in the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution make all of us Americans. The whole world looks to America to hold up the beacon of freedom for the world, just as the Statue of Liberty has been the visible symbol of liberty for millions of immigrants.

This photograph is not famous, but it is one of my favorite vintage photos. Three little boys, friends, sit together in 1930s New York in their wagon—demonstrating the truth that children are not born with racism; to be racist, they must be taught after they are born.

One of the most iconic photographs in American history came during the bloody and hard-fought Battle of Iwo Jima in World War II. Here is the background for the images of this diverse group of Marines who raised the American flag on the hostile Japanese soil from History.com:

“February 23, 1945: During the bloody Battle for Iwo Jima, U.S. Marines from the 3rd Platoon, E Company, 2nd Battalion, 28th Regiment of the 5th Division take the crest of Mount Suribachi, the island’s highest peak and most strategic position, and raise the U.S. flag. . .several hours later more Marines headed up to the crest with a larger flag. Joe Rosenthal, a photographer with the Associated Press, met them along the way and recorded the raising of the second flag along with a Marine still photographer and a motion-picture cameraman.

Rosenthal took three photographs atop Suribachi. The first, which showed six Marines struggling to hoist the heavy flag pole, became the most reproduced photograph in history and won him a Pulitzer Prize. The accompanying motion-picture footage attests to the fact that the picture was not posed. . .three of the Marines seen raising the flag in the famous Rosenthal photo, were killed before the conclusion of the Battle for Iwo Jima in late March.”

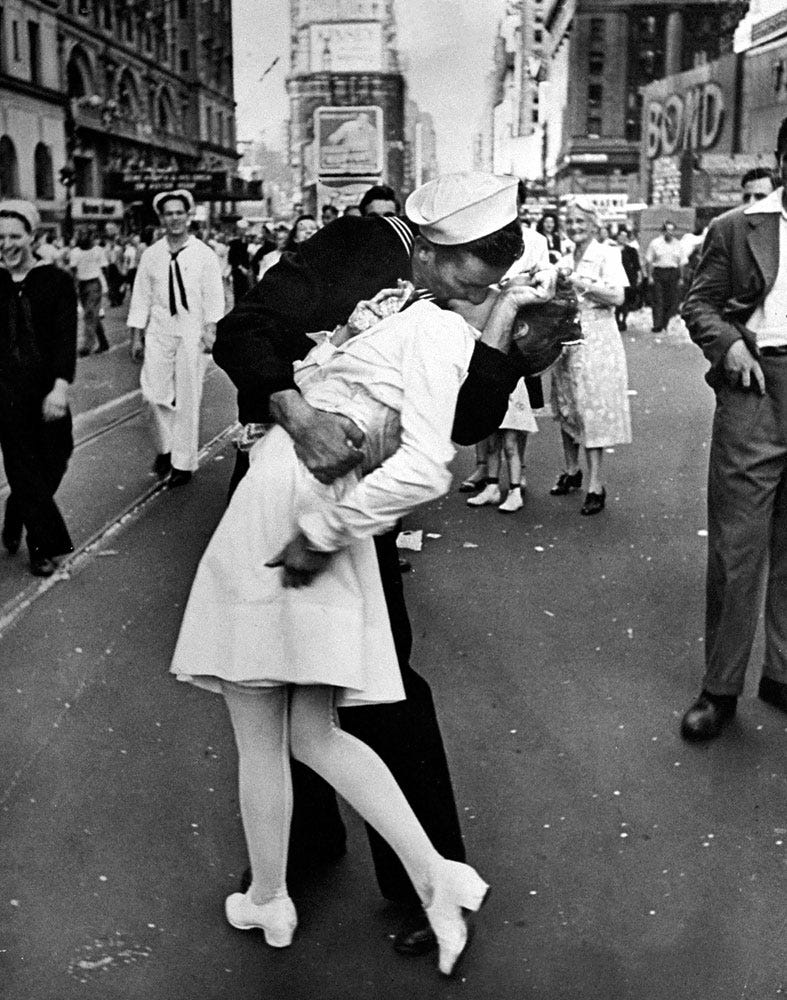

Perhaps the most famous kiss in American history: this sailor kisses a girl in New York City’s Times Square as Americans joyfully celebrate V-J Day, or the day that Japan surrendered in WWII:

Ronald Reagan’s words echoed around the world and spelled the beginning of the end for the Soviet Union in 1987 when he stood in front of the Berlin Wall and said to the Soviet leader, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

Happy Independence Day!

The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses Grant in War and Peace by H.W. Brands, 504