“I got some of the shrapnel — it hit my back and I landed right on my face. I fell down in the sand and thought I was dead,” Lt. Sid Salomon recalled of D-Day. “Right then and there, I said to myself that I wasn’t going to die…We went up on toeholds and by digging our fingernails and bayonets into the cliff.”

(This article includes sections of a piece I originally wrote for PJ Media.)

There are so many inspiring, beautiful stories about the great heroes of American history which are scarcely ever told. One happens on them accidentally—buried in a thick, out-of-print biography, in small print on a museum sign, casually and fleetingly mentioned in an obscure educational video. America cannot return to greatness in the future if we do not truly understand the greatness of our past. That is why I am writing an article series to tell a few of these little-known but moving or illustrative “untold stories” of American greatness. Other articles in this series have included the Indian Prophecy of George Washington’s future greatness; trailblazing Marines throughout U.S. history; how a former slave became “Aunt Jemima,” the first living trademark; and Tim McCoy, actor, army officer, cowboy, and Indian expert and ally.

Today, June 6, is the 79th anniversary of the fateful Allied D-Day landings in Normandy that spelled the beginning of the end for the Nazis. In memory of the thousands of Army and Marine heroes who fought and died that day, I want to highlight six men who stormed the beaches that famous 1944 day: Ellis “Bill” Reed, Woody Doorman, Lt. Dawson, Ray Alm, Lt. Sid Salomon, and John Paul “Jack” Corley.

Historian Patrick K. O’Donnell shared with Breitbart the stories of several heroic members of the U.S. Army Rangers, who led the way on bloody Omaha Beach that morning in 1944. The 2nd and 5th Ranger Battalions, divided into three groups, were set to take Pointe du Hoc and the “deadly” German mortars to Omaha’s far left. As remembered by Ellis “Bill” Reed, General Cota called to his men on Omaha Beach in the words that became the Army Rangers’ motto: “Rangers, lead the way!” And that’s just what the Rangers did.

“We could see the action from the landing craft as we came in,” 5th Ranger Battalion’s Ellis “Bill” Reed remembered. “There was a tremendous amount of firepower coming from both flanks. Machine gun fire and artillery fire was pouring in…When we got off the boat and into the wet sand we had to run for the seawall. Men were dying around us, lying in different positions, and tanks were burning.” Reed ran across about 150 yards of beach, already strewn with the bodies of dead Army Rangers, with his platoon leader and Woody Doorman, a buddy and “bangalore torpedo man,” right beside him.

Reed and Doorman’s job was to torpedo a hole in the concertina wire to allow other men an egress, which they did successfully under heavy fire. “Woody and I had to assemble each piece of the torpedo, get up from behind the seawall, push the Bangalore torpedo across the road on top of the bluff and put it under the concertina wire,” Reed explained. “Once we had the torpedo in place, we took the fuse wire out, pulled the fuse, and yelled, ‘Fire in the hole!’ and jumped back over the wall. The result, if it worked, was a hole in the concertina wire.” Reed worked fast due to the machine gun and mortar fire. “I made sure the fuse lighter went off, since we were told in our training that if it didn’t go off we were to sacrifice our bodies and lay on the concertina wire as the men stepped on us. So I made damn sure that the torpedo detonated,” Reed said, laughing.

Men were now moving through the holes, but still under heavy German fire. “I was told to fire the rifle grenade at a machine gun nest, but like everything else in the U.S. Army, it was a big dud,” Reed detailed the nightmarish situation with a touch of humor. He described the heroism of another Ranger, Lt. Dawson, who successfully charged the German machine gun nest: “So at that point, Lieutenant Dawson got up and charged it with his submachine gun and kept blasting. When we got up close they put their hands up. I remember that one German had his arm dangling by only a piece of flesh. That was our first visual face-to-face contact with the enemy.”

Ranger Ray Alm, who landed on Omaha’s Dog Green Beach, recalled the horrific casualties starting from when the Rangers were wading in to the beach. “We were about two hundred feet from the beach when a shell blew off the front of our landing craft, destroying the ramp,” Alm said of his early morning landing. “My two best buddies were right in front of me, and they were both killed. I was holding a .45 pistol and carrying a bazooka with eight shells; it was so heavy that I just went right under the water. So I had to let everything go except the shells.”

The bloodshed continued as Alm and his comrades reached the beach. “When we were on the beach, there were two other Rangers and myself running, and a German machine gun was firing at us. We hid behind an anti-tank obstacle,” Alm said. “The three of us ducked behind it. We then headed towards the front again. It was terrible; there were bodies all over the place. They wiped out almost the entire 116th Infantry Regiment; they just murdered them. They were floating all over the place, there was blood in the water — it was just dark.” The Army Rangers paid a heavy price for taking the beach.

But come hell, Nazis, or high water, the Rangers were determined to finish their mission. Lt. Salomon was one of the first Rangers on the beach. “The trip was tough coming in,” Salomon said. “Keep in mind, it was postponed due to rough seas. The men started getting sick…We could hear the ping of the machine gun bullets hitting the side of the landing craft, and mortar shells were landing near the landing craft. I could see the concentric circles formed by the shells hitting the water. It was quite something, of course. One of the men joked, ‘Hey, they’re firing at us.’ It added a little humor to the situation.”

Salomon was the first to jump into “not-quite-chest-high water” and the second soldier, Sergeant Reed, was wounded. Salomon dragged Sergeant Reed through the water with him to the beach and then was struck in the back with shrapnel from a mortar shell that “killed or wounded all of my mortar section.” Lying on his face, Salomon decided, “I wasn’t going to die. This was no place to be lying, so I took my maps, I got up, and ran toward the overhang of the cliff.” An aid man dug the shrapnel from his back and Salomon, nothing daunted, began to climb the cliff.

“Each man had a six-foot piece of rope that had a noose at the end of it and, ideally, we were to link the ropes together and scale the cliff,” but there were too many casualties; so “We went up on toeholds and by digging our fingernails and bayonets into the cliff,” said Salomon. Only nine out of 37 men in Salomon’s company survived the climb, and not all of them survived the next phase. He and another Ranger, after throwing a grenade into a German dugout, took a German soldier prisoner. Ultimately, there were too few men to continue inland. “We proceeded to knock out a machine gun section and a mortar section. … We knocked out the German position and figured that we were doing our best by still holding our ground,” Salomon explained.

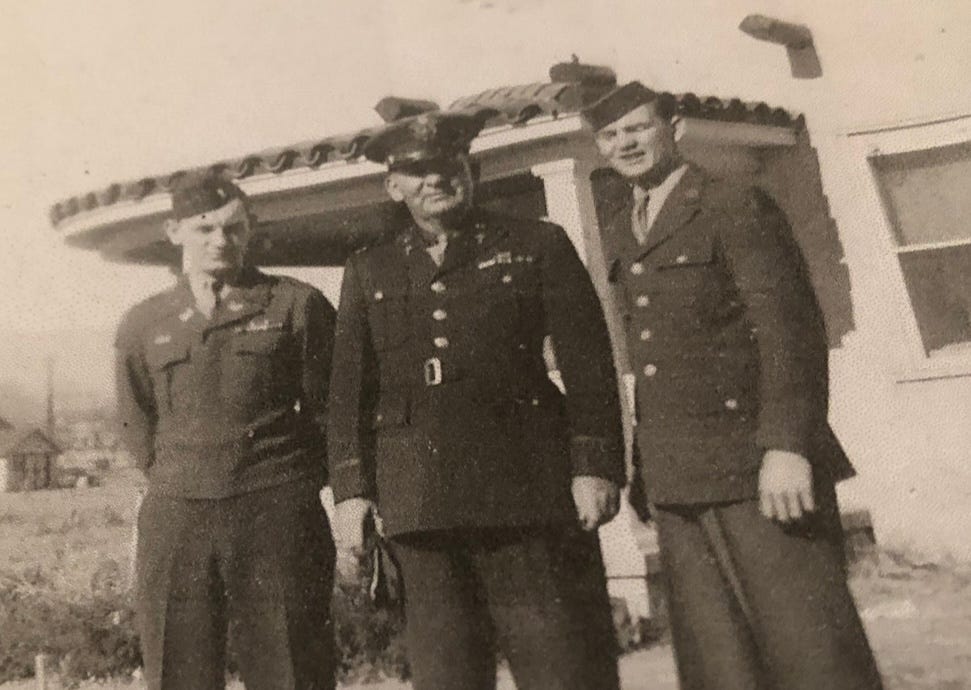

Last but not least is my own great-uncle, Lt. John Paul “Jack” Corley. The Corleys were a patriotic family, with the father and all four sons ultimately serving in the U.S. military (as did three of my grandpa’s children), my grandfather joining just as WWII ended. Jack Corley was an Army engineer with the 5th Engineer Special Brigade, and on D-Day it was his dangerous and unenviable job to disarm the land mines that the Germans had placed on Omaha Beach. Of course, that was after they were landed a mile from where they were supposed to be and had to fight up the beach a whole mile under fire.

One land mine blew up a tank with a young man in it—something Jack never forgot—but Corley and his team successfully disarmed many mines, allowing their fellow Army soldiers to cross the beach and reach the high ground. Jack Corley survived WWII to have two children.

Salomon, Reed, Doorman, Dawson, Corley, and Alm are just six of the thousands of Americans who stormed the beaches of Normandy on D-Day. Today we remember and honor all those who fought and died that day so that freedom could survive in the world.

We’ll always have great men, but we’ll never have better.

We cannot ever forget these men.