Untold Stories: Mack Robinson, Groundbreaking Black Athlete and Born Winner

“Brother of baseball icon Jackie Robinson. Silver medalist behind Jesse Owens. Considered inferior in his own country. But Mack Robinson was a born winner whose legacy continues to this day.” —University of Oregon

There are so many inspiring, beautiful stories about the great heroes of American history which are scarcely ever told. One happens on them accidentally—buried in a thick, out-of-print biography, in small print on a museum sign, casually and fleetingly mentioned in an obscure educational video. America cannot return to greatness in the future if we do not truly understand the greatness of our past. That is why I am writing an article series to tell a few of these little-known but moving or illustrative “untold stories” of American greatness.

Previous articles in this series have included John Callendar, the coward who became a Patriot hero; how George Washington saved a slave family from being divided; how the white citizens of Greencastle, PA saved their fellow black Pennsylvanians from enslaving Confederate invaders; and Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck, the first Native American Indian university graduate. Today, at the close of Black History Month, I want to talk about one of the nearly forgotten greats of American sports, Matthew MacKenzie “Mack” Robinson.

In many ways, Mack Robinson got the short end of the stick much of his life. He was born to a family of sharecroppers in racist Georgia in 1912 and he lost his father at a young age; when the Robinsons moved to California, the racism didn’t improve. He had the opportunity to go to the 1936 Olympics, and took silver in the 200-meter sprint final, breaking the previous Olympic record, as racist Adolf Hitler looked on. But Robinson’s big achievement was overshadowed by the more famous black American athlete Jesse Owens winning gold in that race. Then, though Mack won first in other important competitions, he suffered from severe racism in America and was fired from his job as a street sweeper at one point when the local government fired all its black employees. Mack’s legacy was further overshadowed by his exceptional brother Jackie Robinson, who was the first black man to play in Major League Baseball.

Mack never won the gold medal in the Olympics which he so wanted, and he spent much of his life in relative obscurity in Pasadena, California. But for all that, Mack never let any of his problems kill his spirit or stop him from doing good. His political and social advocacy in his community and elsewhere helped countless young men and women, including his own children. Mack Robinson was a born winner—he never let life beat him.

The University of Oregon, Mack’s alma mater, notes that controversy swirled around the 1936 Olympics, with many people saying the US should boycott the games because they were hosted by Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime. In the end, the US participated, which allowed multiple black athletes to disprove Hitler’s claims that the white “Aryan” race was superior to other races:

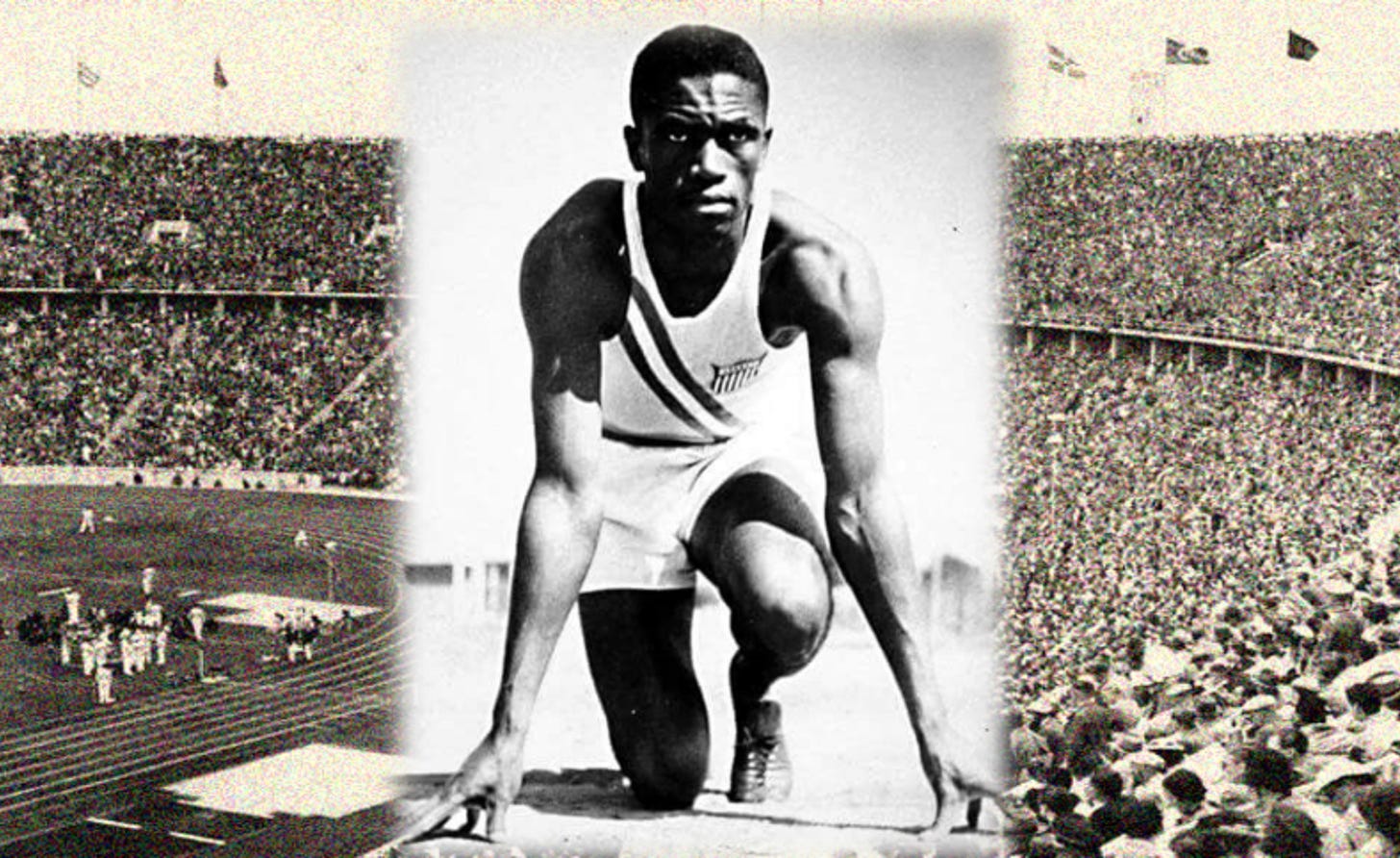

“The Games eventually went ahead—and were the first-ever to be televised, and the first with a torch relay—and on August 5, 1936, the 21-year-old Robinson made his way to the starting line of the Olympiastadion track for the 200-meter final. The 100,000-seat stadium was adorned with swastikas, and Hitler himself was in the crowd, looking on.

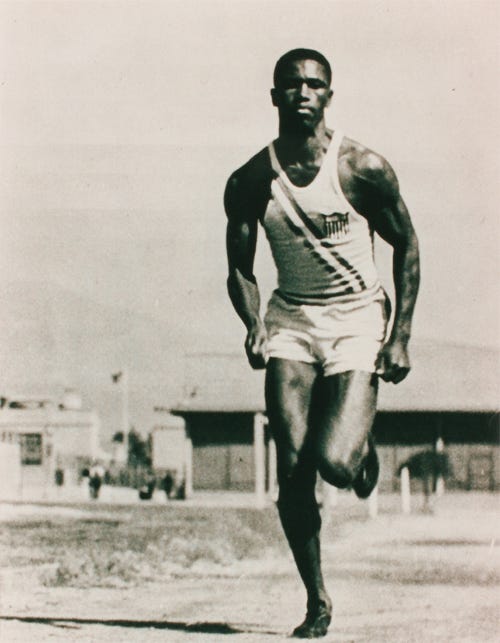

Robinson, wearing the same spikes he’d used to compete for Pasadena Junior College that spring, dug his toes into the divots in the cinder track, looked into the turn ahead of him, and at the sound of the starter’s pistol leapt forward, every sinew in his body straining to pick up every ounce of speed his chiseled frame could muster, legs churning, knees lifted high, arms pumping, elbows back as his wrists brushed past his hips with each blur of a step, around the curve and down the home straight with the roar of 100,000 Germans reverberating inside his head and Dutch sprinter and future SS volunteer Tinus Osendarp on his heels, until he crossed the finish line.

Twenty-one-point-one seconds—approximately the amount of time it took to read the previous paragraph—was all Robinson needed to run 200 meters, equaling the Olympic record he had set in the semifinals. But one step ahead of him, with a new world record of 20.7 seconds and wearing a new prototype of Adidas shoe made by company founder Adi Dassler himself, was J.C. ‘Jesse’ Owens, the Ohio State star who had just claimed the third of the four gold medals he would win in Berlin.”

Robinson’s children contend that if Robinson had had better footwear, he could have beaten Jesse Owens. I don’t know enough to say either way—I would not wish to diminish Owens’s achievement either—but one thing is certain; Mack Robinson proved that he was one of the two best runners for the 200-meter race in the whole world. That’s phenomenal.

In fact, as Mack himself put it, “It's not too bad to be the second best in the world at what you're doing, no matter what it is. It means that only one other person in the world was better than you. That makes you better than an awful lot of people.”

Black American athletes “dominated” Hitler’s Olympics, taking home 14 medals. Hitler, infuriated by this blow to his racist propaganda, called for black athletes to be banned from future Olympics and ranted, “The Americans should have been ashamed of themselves for allowing their medals to be won by Negroes.” Unfortunately, some Americans appeared to agree with that sentiment. Segregation was still very much in force in America and racist Democrat President Franklin D. Roosevelt did not invite any of the black Olympic athletes to the White House, which might that day have taken its name from the only skin color of the athletes FDR hosted. Not all of America was so racist—Jesse Owens was given a Waldorf Astoria reception and ticker tape parade in New York. Mack Robinson, sadly, didn’t get the same recognition.

“Robinson attended Pasadena Junior College for one more year and then transferred to the University of Oregon to study physical education and compete for the Webfoots. In 1938, he won the NCAA and AAU titles in the 220-yard dash for the UO, and was the Pacific Coast Champion in the long jump…Mack had set PJC’s long jump record before leaving for the UO. His younger brother, on the verge of following Mack to Eugene, bested him by an inch, which got the attention of UCLA.”

Mack loved Oregon and apparently had a good experience at university there, so much so that he tried to get his brother Jackie to attend as well. Instead, Jackie was recruited by UCLA and went on to the baseball Major Leagues, fame, and six All-Star honors.

The Robinsons experienced a lot of racism growing up in Pasadena, the University of Oregon says. Jackie Robinson was so furious over the treatment his oldest brother Edgar received that he refused ever to return to the town. Mack summed up his experiences in Pasadena after his Olympic victory, “If anybody in Pasadena was proud for me, other than my family and close friends, they never showed it. I was totally ignored. The only time I was ever noticed was when somebody asked me during at an assembly at school if I'd race against a horse.”

Mack returned after his Olympic triumph, without completing his college degree, so that he could take care of his family, and received no honors. Mack Robinson, the silver medalist, had to take a job as a street sweeper to support the family. Refusing to let the job crush him, he swept the streets wearing his Olympic uniform, so that people would know what he achieved, whether they wanted to or not. Unfortunately, “Robinson lost his job as a street sweeper when Pasadena fired all of its Black employees out of spite after a judge ordered the city to desegregate its public pools.” Once again, life handed Mack Robinson a raw deal.

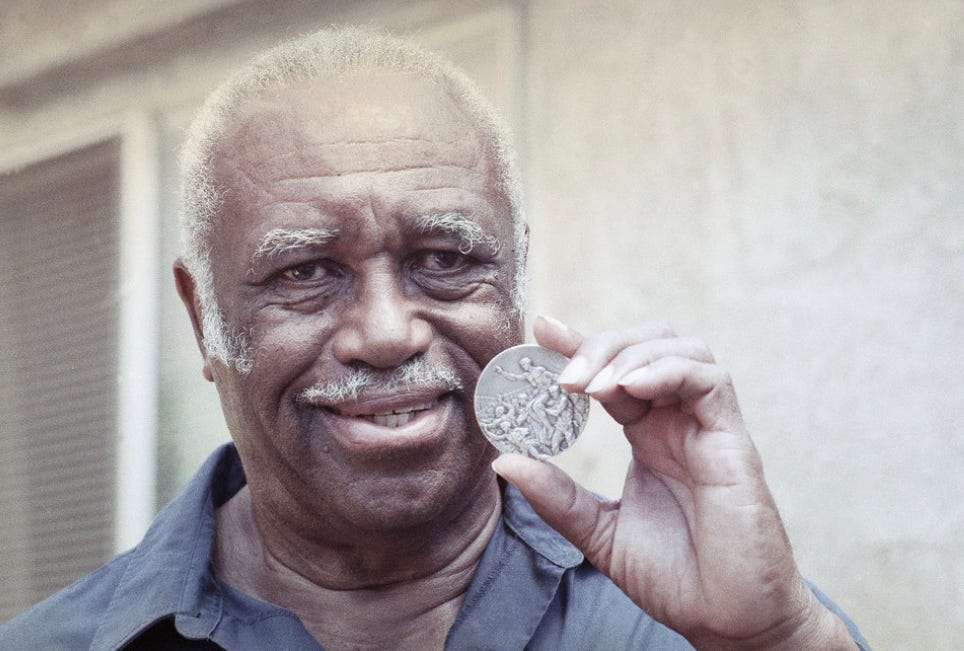

But that didn’t kill Robinson’s spirit. Mack’s kids remembered that the former Olympic athlete was incredibly competitive even in unimportant matters. “For Mack, an Olympic silver medalist and the brother of a baseball legend, competition ran through his veins. His children recall memories of riding in the car with him going 100 miles per hour on the freeway, just to get ahead of another car.” Mack’s son Edward remembered his father saying, “I got a silver medal only because I was just behind Jesse. But understand, I look at my silver medal as a gold medal.” Mack broke the previous Olympic record with his run, and that was a gold medal achievement, even if Owens beat it out.

But that fighting spirit transferred into even more important areas. Mack Robinson never stopped trying to make the world a juster and freer place, and many people felt the good effects of that.

“As an advocate for youth he worked to create opportunities to keep them out of trouble through the creation of playgrounds, YMCAs, and swimming pools, lobbied for better books in the libraries, and was well-known among local lawmakers.

‘By him being a child of, and now resident of Pasadena, my father knew one thing you could do was go down to City Hall, and the word I think he would say was, ‘You could raise a stink,’ said Wayne. ‘He would go down to City Hall whenever there was a planning meeting. My father was so involved with them, they hated to see him come to the…board meetings.’

‘I’ll never forget when I was in the fifth or sixth grade, we were split up when busing came in. And so they asked us in the sixth grade if we wanted to go down to the Board of Education. I thought my dad was going to tell me, ‘No, you can’t go down there and talk to all these Board of Education people.’ Oh no, it was everything but that. ‘Go on down there and voice what you have to say.’ When I got the green light, the green light was on. I told them who I was: ‘I’m Wayne Robinson and I don’t agree with the busing issue and I want to go to my community junior high right here where I can walk to school.’ They said, ‘Who are you? Oh, you’re Wayne Robinson? Oh Lord, this is Mack’s son.’ They were probably sitting in their seats going, ‘Oh my God, here we go. We’ve got to deal with another Mack.’’

‘He fought like no one else could fight,’ said Edward, who remembers passing out fliers with his father to increase involvement in town hall meetings.”

Mack’s generosity and urge to help others was never satisfied. After visiting an aunt in Georgia and seeing her terrible living conditions, Mack rallied aid for her from the Pasadena community. He convinced American Airlines to fly clothes down to Mississippi and Georgia for community centers, churches, and schools.

“Robinson worked tirelessly for the Pasadena community. He demanded that parks were clean, safe, and free of drugs and alcohol. He insisted that pools be made available during the summer months. He volunteered at Lemon Grove Park. In 1992, when riots broke out across Los Angeles after four members of the Los Angeles Police Department were acquitted by a jury after being filmed beating Rodney King, Mack Robinson was one of the community leaders called upon to help restore peace.

‘If you don’t have much guidance, it leaves too much room,’ said Edward of Mack’s motivation for working with Pasadena’s youth. ‘If you don’t have a mentor, you don’t have someone out there saying, ‘No, don’t do that, do this. Why don’t you go here, and don’t go there. Let’s stay at home and don’t go out.’”

Mack finally received some recognition for his achievements later in life, as IMDb explains:

“[Robinson] went on to work as both an usher at Dodger Stadium and as a truant officer for John Muir High School in Pasadena. In 1984 Mack was one of several athletes chosen to carry a giant Olympic flag into the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum during the opening ceremony for the 1984 Olympics. In 1997 both Robinson and his brother Jackie were honored with nine foot tall bronze sculptures of their heads in Centennial Plaza located right across the street from city hall in Pasadena. In addition, Mack was inducted into both the Oregon Sports Hall of Fame and the University of Oregon Hall of Fame. Robinson died at age 85 at a hospital in Pasadena on March 12, 2000. He was survived by his wife Delano, their three sons and three daughters, a son and daughter from previous marriages, twenty-five grandchildren, and eight great grandchildren.“

Mack Robinson always insisted on maintaining his connection with the Olympics. “Daddy got invitations to go places to speak with the Olympics,” remembered his daughter Kathy. He’d take the whole family. He also wanted to help others whose lives had given them tough handicaps to achieve their Olympic dreams.

“Robinson stayed involved with the US Olympic Committee, and in 1984 was chosen to be one of the athletes who would carry the Olympic flag into the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum during the opening ceremony for the Olympic Games. His love of the Olympic spirit also fueled him as a fan. A vocal supporter of the Special Olympics, Robinson volunteered his time and would applaud the athletes during meets and take photos of them—again, with his children in tow.

‘He was always cheering them on, saying ‘Rah rah rah,’’ recalled Kathy.”

And that was Mack Robinson. A man who had dreams and pride in himself even when he was treated most shamefully. A man who believed he was a winner no matter how others tried to keep him down. A man who made his family and his community the center of his life, who was always most interested in helping others even when others showed the least interest in helping him.

Far more even than being an Olympic medalist and groundbreaking athlete, Mack Robinson was a great and good man. And that is the best award any man can win.