Untold Stories: John Fitzgerald, Irishman, Revolutionary, and Friend of George Washington

Irish Catholic John Fitzgerald was George Washington’s friend before the Revolution, his “favorite aide” during the Revolution, and a hero of American history; “ever one constant and faithful in devotion” to America.

There are so many inspiring, beautiful stories about the great heroes of American history which are scarcely ever told. One happens on them accidentally—buried in a thick, out-of-print biography, in small print on a museum sign, casually and fleetingly mentioned in an obscure educational video. America cannot return to greatness in the future if we do not truly understand the greatness of our past. That is why I am writing an article series to tell a few of these little-known but moving or illustrative “untold stories” of American greatness.

Previous articles in this series have included Native American Indian soldiers who helped shape America’s history; the “Battle of Princeton” painting by William Mercer, America’s first deaf artist; how a former slave became “Aunt Jemima,” the first living trademark; how Union Col. Trimble saved black freemen from Confederate enslavers; and local, little-known heroes who remind us that we have always been a nation of heroes. Today I want to talk about one of the many Irish Catholic heroes of the American Revolution, a close friend of George Washington, and an invaluable eyewitness recorder of history.

In the book George Washington and the Irish, Niall O’Dowd tells the story of Washington’s lifelong friend John Fitzgerald, the Irish Catholic immigrant to Virginia who became an Aide-de-Camp to Washington during the Revolution and wrote diary entries which provide very valuable information about the famous Delaware River crossing on Christmas Night, 1776. Fitzgerald continued to be Washington’s friend after the war and the latter’s last public engagement outside his Mt. Vernon residence before his death was a dinner in Alexandria in November 1799 with Fitzgerald.

Fitzgerald was a native of Wicklow County, Ireland, born around 1750, who emigrated to America in 1769. He was close with the Jesuits, who at the time were a great force for reform and evangelization (unlike the modern Jesuits). This might indicate that he was educated in France by Jesuits, as were many Irish Catholics who had some money, since the tyrannical British Penal Laws forbade any Catholic education at all in Ireland.

Fitzgerald was a rising business man and a social favorite in Alexandria, Virginia, where he was elected a Burgess or councilman in 1770, soon after his arrival. He was a great favorite with the local ladies and married into a family that lived close to George Washington, which might explain how they became friends. Fitzgerald is recorded as having visited Washington’s home no fewer than 80 times (based on Washington’s own diary), indicating the intimacy of the friendship between the Irish Catholic immigrant and the Anglo Protestant soldier.

Washington wanted the younger man by his side during the Revolution, too. Niall O’Dowd says Fitzgerald stood beside Washington as the latter took command of the Continental Army in 1775, and Fitzgerald then joined the Army himself as Aide-de-Camp to the commander-in-chief, a position that, according to Washington himself, required a person “in whom entire confidence must be placed.” In November that year, Fitzgerald was appointed Washington’s secretary. The young man who had been a prominent and prosperous business man in Alexandria was fighting for principles rather than personal gain, because he only made $33 monthly, then later $40 a month as lieutenant-colonel. Washington’s adopted grandson George Washington Parke Custis said Fitzgerald was Washington’s “favorite aide,” a great testament, especially light of the fact that Fitzgerald was competing with the likes of Alexander Hamilton. Historian Martin Griffin writes:

“In all the operations of the army, Colonel Fitzgerald from 1776 to 1782, save occasional leaves of absence, and then for military purposes, is found constantly by the side of Washington, especially in action. Nor does he appear among those who with ‘promptness seek preferment’ because of hard duty and inadequate pay; but ever one constant and faithful in devotion to his adopted country and with fidelity and affection for the Commander-in-Chief.”

Fitzgerald’s journal entries during and after that history-changing Christmas Night, 1776, are fascinating reading, as providing a first-hand account of the Battle of Trenton, a turning point in the American Revolution. I have copied out parts of those entries below, as found in O’Dowd’s book:

“Christmas, 6 P.M. … It is fearfully cold and raw and a snow-storm is setting in. The wind is northeast and beats in the faces of the men. It will be a terrible night for the soldiers who have no shoes. Some of them have tied old rags around their feet, but I have not heard a man complain … I have never seen Washington so determined as he is now … He stands on the bank of the stream, wrapped in his cloak, superintending the landing of the troops. He is calm and collected, but very determined. The storm is changing to sleet and cuts like a knife…

[3 A.M.] I am writing in the ferry house. The troops are all over, and the boats have gone back for the artillery. We are three hours behind the set time … [the Marbleheader regiment directing the boats] have had a hard time to force the boats through the floating ice with the snow drifting in their faces.”

Fitzgerald was clearly right by Washington the whole time—meaning he was also in the forefront of all the action that day. An exchange he recorded in his diary makes that clear.

“It was broad daylight when we came to a house where a man was chopping wood. He was very much surprised when he saw us. ‘Can you tell me where the Hessian picket is?’ Washington asked. The man hesitated, but I said, ‘You need not be frightened, it is General Washington who asks the question.’ His face brightened, and he pointed toward the house of Mr. Howell.

It was just eight o’clock. Looking down the road I saw a Hessian running out from the house. He yelled in Dutch [Fitzgerald probably meant Deutsch or German] and swung his arms. Three or four others came out with their guns. Two of them fired at us, but the bullets whistled over our heads. Some of General Stephen’s men rushed forward and captured two. The others took to their heels, running toward Mr. Calhoun’s house, where the picket guard was stationed, about twenty men under Captain Altenbockum. They came running out of the house. The captain flourished his sword and tried to form his men. Some of them fired at us, others ran toward the village.

The next moment we heard drums beat and a bugle sound, and then from the west came the boom of cannon. General Washington’s face lighted up instantly, for he knew that it was one of [General John] Sullivan’s guns.”

Another Founding Father who was an artillery officer at Trenton was Alexander Hamilton, only 21 when he assisted at the historic battle. Yet another Founding Father and future president was mentioned by name in Fitzgerald’s continued narrative below.

“We could see a great commotion down toward the meeting house, men running here and there, officers swinging their swords, artillerymen harnessing their horses. Captain Forrest unlimbered his guns. Washington gave the order to advance, and rushed on to the junction of King and Queen streets. Forrest wheeled six of his cannons into position to sweep the streets. The riflemen under Colonel Hand and Scott’s and Lawson’s battalions went upon the run through the fields on the left to gain possession of the Princeton Road. The Hessians were just ready to open fire with two of their cannons when Captain [William] Washington and Lieutenant [James] Monroe with their men rushed forward and captured them.

We saw [Hessian commander Colonel Johann] Rall riding up the street from his headquarters, which were at Stacy Potts’ house. We could hear him shouting in Dutch, ‘My brave soldiers, advance.’

His men were frightened and confused, for our men were firing upon them from fences and houses and they were falling fast. Instead of advancing they ran into an apple orchard. The officers tried to rally them, but our men kept advancing and picking off the officers. It was not long before Rall tumbled from his horse and his soldiers threw down their guns and gave themselves up as prisoners…

[9 P.M.] I have just been with General Washington and [Nathanael] Greene to see Rall. He will not live through the night. He asked that his men might be kindly treated. Washington promised that he would see they were well cared for.”

The fact that the Hessians were indeed well cared for is a great testament to the virtue of Washington and his men, including Fitzgerald, since the Hessians had previously and noticeably slaughtered en masse American soldiers who surrendered to them on more than one occasion. The Hessians understood the greatness the Americans showed by the kind treatment they received—as evidenced by the fact that as much as half of all the Hessian troops the British brought to fight the Patriots stayed in America after the Revolution. Fitzgerald was an invaluable witness and recorder of that greatness of Washington’s, as he was of the heroism of all the American soldiers that snowy winter day at Trenton.

But while the Delaware River crossing has become iconic in American history, the other victories of that remarkable campaign—a campaign which won Washington the unwilling but high admiration of his enemies both in America and Europe—are little known. The Battle of Princeton was an unplanned clash that resulted in American victory mere days after the Delaware crossing. Washington lost one friend at Princeton, Hugh Mercer, but it became a key point in the life of his other friend, John Fitzgerald. O’Dowd explains:

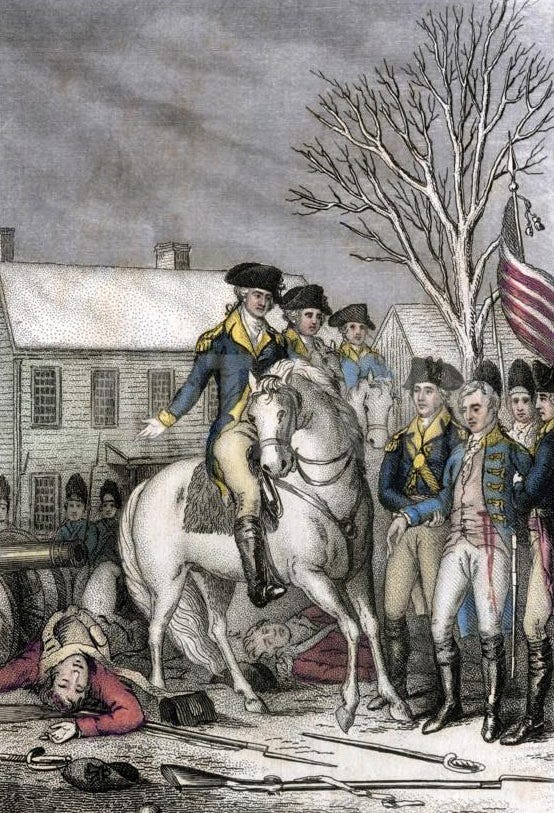

“Fitzgerald witnessed one of Washington’s greatest moments in battle. The Catholic World describes it as ‘the most graphic incident of Fitzgerald’s connection with the great commander.’ The incident in question, a scene at the battle of Princeton, was described by George Washington Parke Curtis, the adopted son of Washington, in his memoirs: ‘We have often enjoyed a touching reminiscence of that ever memorable event from the late Colonel Fitzgerald, who was aide to the chief, and who never related the story of his general’s danger without adding to his story the homage of a tear.’

Washington’s army, between Trenton and Princeton, encountered two British battalions and the fighting was fierce. The Americans were being driven back until Washington urged his steed forward to better direct his army’s musket fire. Washington was now out in front of his men and a despairing Fitzgerald watched as the bullets flew closer. Finally, Fitzgerald could take it no more and, convinced Washington would be shot by either friendly fire or British muskets, buried his face in his hat, unable to watch.

He was aroused a few moments later by Washington riding up to him unscathed. The tough young Irishman broke down in tears … Washington smiled and grasped his young friend’s hand and simply said, ‘The day is ours.’”

Fitzgerald’s fear for Washington was highly reasonable. Not only was the fighting at Princeton fierce, but it was common for soldiers in the Revolutionary Army to aim particularly for officers, as noted by Fitzgerald himself in his Trenton journal entries. Washington, well over six feet tall and famed as a large and eye-drawing figure, would have looked a big and easy target on the battlefield.

Furthermore, while Washington was so miraculously preserved at Princeton, his friend Hugh Mercer was viciously and brutally killed by British soldiers after his capture, under the mistaken belief that Mercer was Washington. That moment of fear and gratitude on the battlefield of Princeton evidently had a profound effect on Fitzgerald, and probably made him love the older Washington more than ever. We know the Irishman and “his general” stayed good friends their whole lives, and that one of Washington’s last acts before he died was to dine with Fitzgerald, as noted above. They were also recorded as dining together on St. Patrick’s Day 1788, and celebrating together on July 4, 1799, when Washington complimented Fitzgerald’s military display that day.

Fitzgerald died not long after Washington, and is buried in a Catholic cemetery in Alexandria, on the road to Washington’s home Mount Vernon. He always guarded “his general” in life, and he continues to guard the road to the General’s home in death.