This article is an expanded version of one I originally published last year as part of my Untold Stories series. Since it is a wonderful story with both cultural and historical significance, I am posting it again this year with additional information.

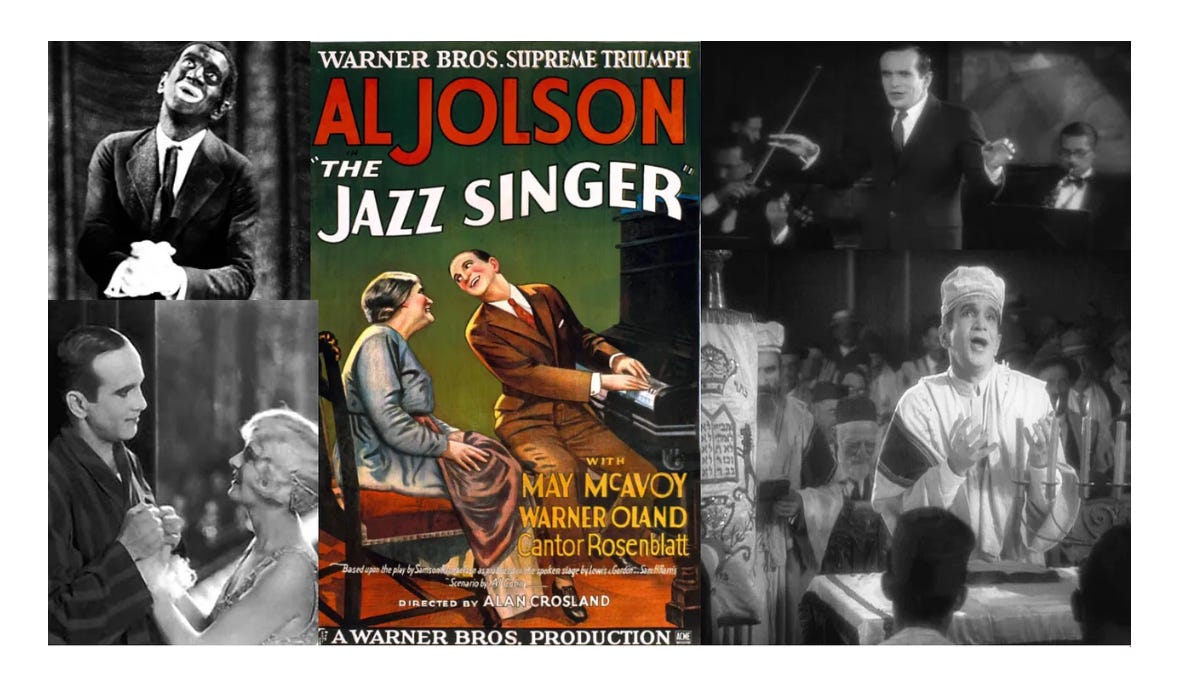

Today (Oct. 6) marks the 1927 premier of the first “talkie,” or the first movie with sound. “The Jazz Singer” starred the legendary Al Jolson, once called “the world’s greatest entertainer,” in a story of how “The son of a Jewish Cantor must defy the traditions of his religious father in order to pursue his dream of becoming a jazz singer.”

The movie (which was technically a “part-talkie,” some scenes silent and others with sound) marked a monumental turning point in the history of movies, with sound synced up to the lip movements of the actors and singers, marking the beginning of the end of the silent movie era and the dawning of the golden age of Hollywood. Popular entertainment would never be the same.

New York critic Robert Sherwood recalled, “Its first performance in New York called forth such enthusiasm as I have never seen before in a film parlor…Everyone wept, including Al Jolson himself, who was called upon for a speech after the final fadeout. He was too overcome to tell the audience (his usual farewell), ‘Folks, you ain’t seen nothin’ yet.’”

According to an article on the Library of Congress website, by March, 1928 it was showing in 235 theatres and by 1931 had earned $2 million, almost five times its $422,000 budget.

Adjusted for inflation, that’s over $41 million.

Jolson has been canceled in modernity because he reached fame doing blackface routines (below is one such from “The Jazz Singer”). While we now rightly see black face as offensive, not everyone who did it then was racist; some even saw it as a sort of tribute to black Americans and a way to tell the story of their suffering (strange as that seems now). Bing Crosby did blackface more than once, and he was a staunch and key supporter of civil rights, with legendary black musician Louis Armstrong as one of his closest friends.

In fact, Al Jolson had many black friends, one of them the talented dancer “Bojangles” Robinson, and Jolson battled racial discrimination both on Broadway and in movies. He fought for equal treatment and desegregation, and promoted black performers on stage and in film. Jolson invited black performers to his home (at a time when few white stars did so) and took them to supper. There were lots of black actors who came to Jolson’s funeral; to them, he was not an image of racism, but a friend and a champion.

For Jolson, Bojangles, and many others, there did not seem at the time a complete contradiction between Jolson performing in blackface and then demanding an end to racist prejudice. In fact, the title of “The Jazz Singer” highlights how Jolson provided a transition to a less prejudiced appreciation of black performers’ music; after all, that’s what jazz was! Jolson was bringing black culture into the mainstream. But “The Jazz Singer” also helped celebrate Judaism and Jewish Americans in a massively popular way. We might look back and see prejudice of one type, but the movie undoubtedly was a work of art that could fight anti-Semitism (see below).

Jolson was a Jew who had left Lithuania (then under the control of the anti-Jewish Russian empire) and come to America as an immigrant. Even in America, there was too much anti-Semitism in many sectors of society. Jolson understood the reality of prejudice. But he also knew that America was the best country in the world for breaking down obstacles and succeeding.

Jolson was enthusiastically patriotic; he tried to enlist in the military during the Spanish-American War at the age of 14, sold war bonds in WWI, and entertained troops during WWII and the Korean War. Just as he went from being a poor immigrant to a superstar, Jolson wanted black Americans to have that chance too.

From Wikipedia:

As early as 1911, at the age of 25, Jolson was noted for fighting discrimination on Broadway and later in his movies.[129] In 1924, he promoted the play Appearances by Garland Anderson[130] which became the first production with an all-black cast produced on Broadway. He brought a black dance team from San Francisco that he tried to put in a Broadway show.[129] He demanded equal treatment for Cab Calloway, with whom he performed duets in the movie The Singing Kid.[129][see below]

Jolson read in the newspaper that songwriters Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle, neither of whom he had ever heard of, were refused service at a Connecticut restaurant because of their race. He tracked them down and took them out to dinner, "insisting he'd punch anyone in the nose who tried to kick us out!"[12] According to biographer Al Rose, Jolson and Blake became friends and went to boxing matches together.[131]

Film historian Charles Musser notes, "African Americans' embrace of Jolson was not a spontaneous reaction to his appearance in talking pictures. In an era when African Americans did not have to go looking for enemies, Jolson was perceived a friend."[132]

So today we celebrate Al Jolson. Unlike most actors in Hollywood—including the overwhelming majority of modern actors who would condemn blackface as unforgivable—Jolson was not just a talented performer. While he may have attained fame with a performance we now condemn, Jolson used his fame to do a lot of good, particularly for his black friends. Here’s to “The Jazz Singer” and its star, the iconic Al Jolson.