“‘Hell or Connaught’ were the terms he thrust upon the native inhabitants, and they for their part, across three hundred years, have used as their keenest expression of hatred ‘The Curse of Cromwell on you.’ … Upon all of us there still lies ‘the curse of Cromwell’.” —Winston Churchill

“You ask what — I have found, and far and wide I go:

Nothing but Cromwell's house and Cromwell's murderous crew.” —William Butler Yeats, “The Curse of Cromwell”

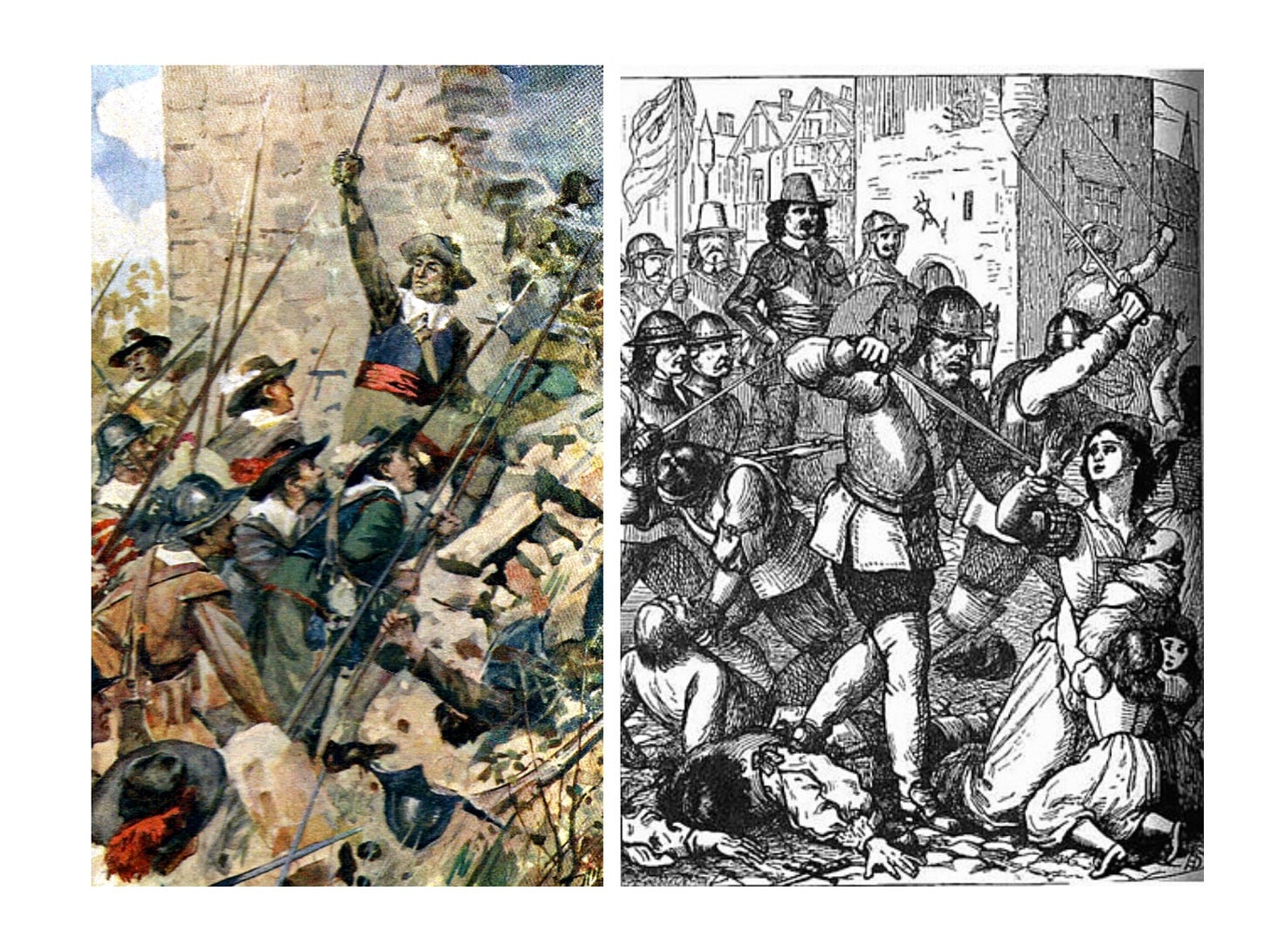

On Sept. 3, 1649, the Siege of Drogheda began. Oliver Cromwell, the Puritan dictator who had killed a king and led a successful coup of the English government, was now knocking on Drogheda’s gates in Ireland. His tyranny and bloodshed he would not restrict to England; Scotland and Ireland, though most especially Ireland, would suffer the “curse of Cromwell.”

This evil and intolerant tyrant had said, “Catholicism is more than a religion, it is a political power. Therefore I’m led to believe there will be no peace in Ireland until the Catholic Church is crushed.” And he meant it, with every fiber of his being, as the unfortunate inhabitants and defenders of Drogheda were all-too-soon to find out. Some 200,000 Irish are estimated to have been killed during the era of Cromwell’s Commonwealth, with another 50,000 sold into indentured servitude, out of a population of 2 million; and Drogheda was an infamous massacre, horribly illustrative of Cromwell’s policies and attitudes that led to the deaths of so many during his rule.

St. Luke’s Historic Church and Museum notes that the “years from 1649 to 1660, which constituted the period of the Commonwealth of England, were extraordinarily violent.” Even in an age where tyranny, mass murder, and military or governmental abuses were the norm across much of the world, the cruelty of Cromwell and his fellow power-hungry, self-righteous Parliamentarian Roundheads was shocking.

Cromwell’s excuse—if such a term could be accurately applied—was the Irish rebellion of 1641. Many of our sources on that still-controversial conflict are Anglo Protestants; that is, the very same men whose theft of Irish lands and homes from the natives not unnaturally roused the outrage of those natives. Undoubtedly there were bloody killings from both sides; the Irish, suffering so long under the yoke of English tyranny, burst forth in bloodthirsty violence against the foreign settlers, leaving thousands of the latter dead or homeless. In any case, the violence was visited back on the Irish Catholics again, according to The Irish Story, which claims that Charles I’s English and Scottish armies “paid back, with at least equal ferocity, the massacres of Protestants in 1641 on the Catholic population.”

Ironically, King Charles I too would soon find himself on the scaffold, the victim to the anti-monarchical and religiously fanatical brutality of the Parliamentarians. And then the “curse of Cromwell” came to Ireland, as the “New Model Army” set out to destroy a newly-formed alliance, per St. Luke’s: “the Irish Confederacy, made up of Irish Catholics and Royalists in exile.” The Irish Catholics and the Anglo-Royalists, along with the Ulster Scots, discovered that they all opposed Cromwell and wished to save Ireland from his oppressive rule. The Cromwellians hypocritically avowed their dedication to religious freedom and liberty of conscience while simultaneously imposing an exceptionally oppressive religious tyranny. Thus the united Irish and Royalist forces under Arthur Aston found themselves at Drogheda making a last stand.

Aston would not surrender; considering the result of the siege, it is highly doubtful if his surrender would have done anything other than ensure a death of ignominy without even attempting a brave resistance first. On Sept. 3, the Siege of Drogheda began, and on Sept. 11, Cromwell’s siege guns had opened two breaches in the city’s walls. The Parliamentarians climbed up collapsed masonry to meet “tenacious” resistance from the defenders, according to The Irish Story. When a Royalist colonel was killed, however, the Parliamentarians were able to break through. What immediately followed was “a rout and then a massacre,” as the Parliamentarians raged through the town, murdering soldiers and civilians, sacking churches, and launching themselves passionately into the execution of a devastating war crime. Even Britannica admits the “carnage inside the city was appalling. Cromwell’s troops killed priests and monks on sight.” The “effusion of blood” Cromwell had threatened was flowing.

From Cromwell himself we hear the callous description, “In the heat of the action, I forbade them [his soldiers] to spare any that were in arms in the town…and, that night they put to the sword about two thousand men.” Aston and 200 of his Royalists surrendered on the promise of receiving their lives, and were then murdered by the treacherous, lying Parliamentarians. As Cromwell coldly put it, his men “were ordered by me to put them all to the sword.” In fact, Aston was beaten to death with his own wooden leg, according to Britannica, and many others were likewise clubbed to death.

[The Irish Story] Another 80 Royalist soldiers who were holding out in [Catholic] St Peter’s Church were burned to death when the Parliamentarians set fire to the Church. The final major concentration of Royalist soldiers was 200 men, stationed in two towers at the walls. They stayed in the towers during the sack of the town but surrendered the following day, September 12. All of the officers and one in every ten ordinary soldiers were killed by being clubbed to death The rest were deported to Barbados.

How many civilians died in the sack of Drogheda has never been determined…Cromwell spoke of a total of 3,500 dead at Drogheda of whom 2,800 were soldiers – indicating that about 7-800 of the dead were civilians. One Protestant congregation in the town were huddled in the house of their Cleric when New Model soldiers burst in, firing their muskets and killing one of their number.

English Catholics, Irish Catholics, and Royalist Protestants all fell victim to the mass murdering Parliamentarians. The curse of Cromwell had fallen on Drogheda and the screams of its victims echo till the present day. “The savagery at Drogheda was replicated at Wexford the following month and Clonmel the next May. By the time Cromwell had put down the rebellion and returned to England in that same month, he had become forever hated by Irish Catholics,” Britannica states. It estimates that, of the 3,100 Irish/Royalists, 3,000 were either dead or captured.

It is no wonder that British statesman Winston Churchill sorrowfully observed of the Irish that they “have used as their keenest expression of hatred ‘The Curse of Cromwell on you.’”