Holy Thursday: The Eucharist Makes Us Like Christ

“And whilst they were at supper, Jesus took bread, and blessed, and broke: and gave to his disciples, and said: Take ye, and eat. This is my body. And taking the chalice, he gave thanks, and gave to them, saying: Drink ye all of this. For this is my blood of the new testament, which shall be shed for many unto remission of sins.” —Matt. 26:26-28

“And taking bread, he gave thanks, and brake; and gave to them, saying: This is my body, which is given for you. Do this for a commemoration of me. In like manner the chalice also, after he had supped, saying: This is the chalice, the new testament in my blood, which shall be shed for you.” —Luke 22:19-20

“And whilst they were eating, Jesus took bread; and blessing, broke, and gave to them, and said: Take ye. This is my body. And having taken the chalice, giving thanks, he gave it to them. And they all drank of it. And he said to them: This is my blood of the new testament, which shall be shed for many.” —Mark 14:22-24

Today is Holy Thursday 2023, the day in the Bible on which Jesus has the Passover meal—His Last Supper—with His disciples, and on which He consecrates for the first time the Holy Eucharist (the Body and Blood of Jesus, under the appearance of bread and wine). On this most significant Christian feast day, I would like to look at a few verses from John 6 on the importance of the Eucharist and then tell an interesting story about Leonardo da Vinci’s experience with the models he used to paint his world-famous “Last Supper.”

Jesus Christ said in John 6:54, “Amen, amen I say unto you: Except you eat the flesh of the Son of man, and drink his blood, you shall not have life in you.” Unless we partake of the Eucharist, we cannot have life eternal. That is what Jesus said. St. Paul emphasized (1 Cor. 11:27, 29) how vitally important the Eucharist was when he noted that receiving the Eucharist unworthily condemns one to Hell. “Therefore whosoever shall eat this bread, or drink the chalice of the Lord unworthily, shall be guilty of the body and of the blood of the Lord…For he that eateth and drinketh unworthily, eateth and drinketh judgment to himself, not discerning the body of the Lord.” This is not the language of symbolism. This is the language of reality, of Jesus physically present in the Eucharist. We must “discern” Jesus’s body really present in the seeming bread.

And yet how many Christians today, just like the Jewish followers of Christ in John 6, walk away from this Eucharistic doctrine and deny it, murmuring as was said by Jesus’s followers then, “This saying is hard, and who can hear it?” (Jn. 6:61). Some point to John 6:64 (Douay Rheims edition), where Jesus says, “It is the spirit that quickeneth: the flesh profiteth nothing.” First of all, if this really disproved the reality of the Eucharist, it seems ridiculous that Jesus should waste an entire sermon telling people His flesh is necessary for salvation before immediately contradicting Himself and saying—just kidding, flesh profits nothing. Secondly, Jesus is described as losing many followers because He says His Body and Blood are food and drink. How strange, how fantastical, if He meant it only figuratively, that He should have let a large number of His followers leave believing His words were literal, when a simple clarification could have told them it was figurative! But Jesus doesn’t do that. He lets them leave him, because His words were literal. In fact, in John 6:53, the astonished Jews ask, “How can this man give us his flesh to eat?” Again, instead of correcting a literal interpretation, Jesus doubles down.

Thirdly, whereas before Jesus said His flesh was necessary for salvation, in John 6:64 he says the flesh profits nothing. In other words, while His flesh gives life, flesh as mere material, or as a word used to symbolize the world, does not profit us. The verse actually supports the immense importance of the Eucharist—only Jesus’s living flesh can bring us the greatest spiritual goods, whereas the world can offer no salvation.

Finally, the Greek word (that is, the original word used by St. John) in John 6:54 does mean “eat,” but that doesn’t capture the full meaning. The word used here, φαγητε (phagaete—a form of ephagon), is from the aorist (past tense) stem of the verb εσθιω (esthio), which, besides “eat,” means to “devour.” And if that weren’t physical enough for you, in John 6:55 Jesus uses an almost hyper-visceral word, τρώγων (trogon), from τρώγω (trogo), which means quite literally to “gnaw,” “chew,” or “crunch.” In later Greek (I am not certain exactly when), τρώγω was also used as the present tense of εφαγον (ephagon), so the two words are connected anyway.

Thus, more accurately, John 6:54-55 says, “Amen, amen I say unto you: Except you devour the flesh of the Son of man, and drink his blood, you shall not have life in you. The one gnawing on [or chewing] my flesh, and drinking my blood, hath everlasting life: and I will raise him up in the last day.”

The ancients speak of how eating makes the food a part of oneself. By eating bread, for instance, I assimilate the bread with my own body, and it becomes part of my body. This is true in a more mystical way with the Eucharist—by consuming Jesus’s flesh and blood, He not only becomes a part of us, but we become a part of Him. The Eucharist is sometimes called “Holy Communion,” because in receiving it devout Christians become united to Christ in the very closest and most intimate type of Communion or union. When receiving the Eucharist, the Church as “Body of Christ” is not only a spiritual reality, but a physical reality.

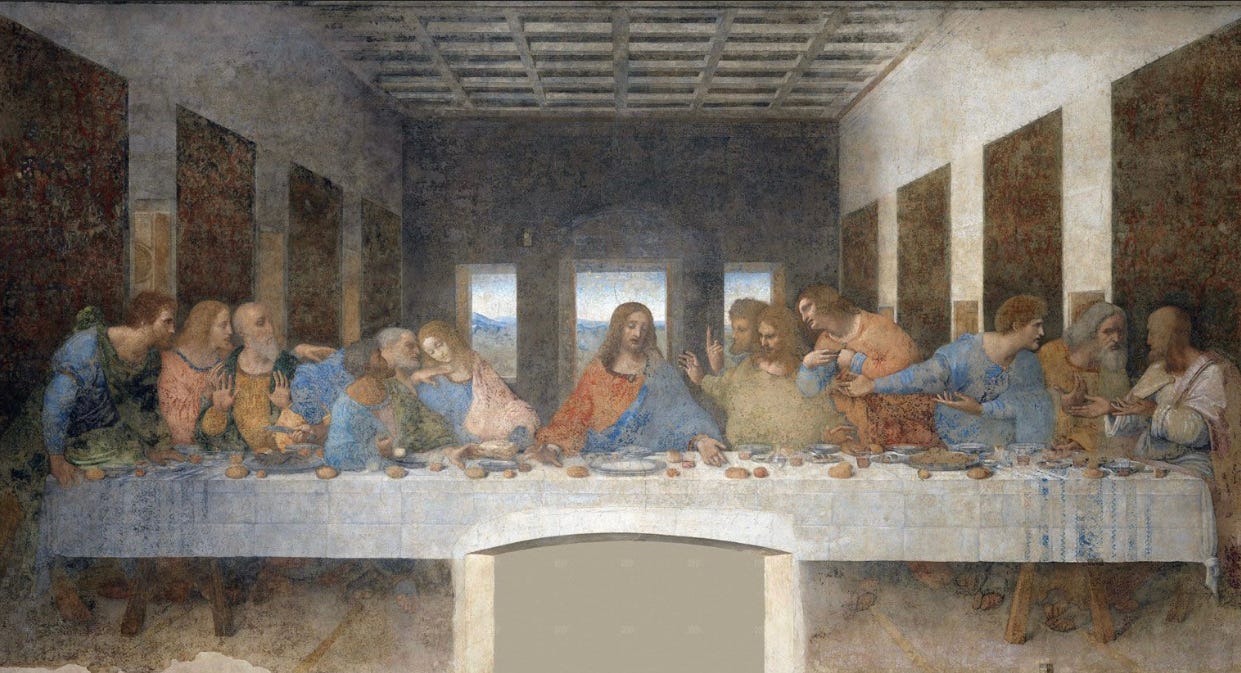

The most famous image of the Last Supper, interestingly enough, does not depict the exact moment of the consecration of the Eucharist, but rather the point when Jesus predicts one of the apostles will betray him (Matt. 26:21-25). The apostles draw back or lean forward in astonishment and concern, asking, “Surely it is not I, Lord?” Judas, the betrayer, already grasps the money for which he betrayed Christ in his hand. The image, of course, is the famous wall painting of The Last Supper for a Milanese monastery by Leonardo da Vinci.

There is a story told about this painting. Whether it is true or not is contested—the story usually records ten years of work to complete the painting, while most sources say Leonardo only took about four years (starting 1495). Possibly it is a blend of truth and fiction. But whether fact or fable, the tale provides an excellent meditation for Holy Week.

The story goes that Leonardo da Vinci, searching for models for the figures in his painting, found a man young, strong, and handsome, who seemed to radiate holiness and peace from his face. Leonardo eagerly chose the man to model for Jesus. He was perfect. After the man had modeled for him, Leonardo lost track of the youth.

But some years later, Leonardo was searching in frustration for a man who looked like the perfect villain, like the ultimate traitor, Judas Iscariot. So the artist searched the prisons, examining each criminal’s face. At last he found a man who looked to him the very picture of villainy, and he arranged that the man would sit for him as a model for Judas Iscariot.

When Leonardo was done, the criminal asked if he could look at the painting. As he did so, tears began to run down his cheeks. The criminal revealed to Leonardo he was the very same man who had sat as a model for Jesus years ago! After that time, the felon fell into sin and crime. His earlier goodness and promise were corrupted, and at last he became the criminal he was at that time.

Again, whether the story is fully true or not, it speaks one undeniable truth—that every man is able to be corrupted, and will be corrupted, unless he makes God the center of his life. But Jesus can save anyone, even a criminal or traitor, if only he asks for forgiveness. And just as that man went from being an image of Jesus to an image of Judas, just so every one of us can go from being an image of sin to being the image of Christ, through humility, virtue, and union with Christ in the Eucharist.